Finding our family in the archives – James O’Grady and the Asylum

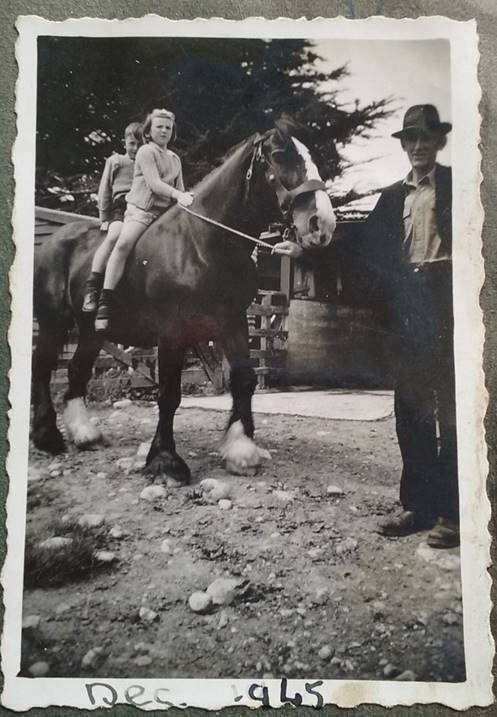

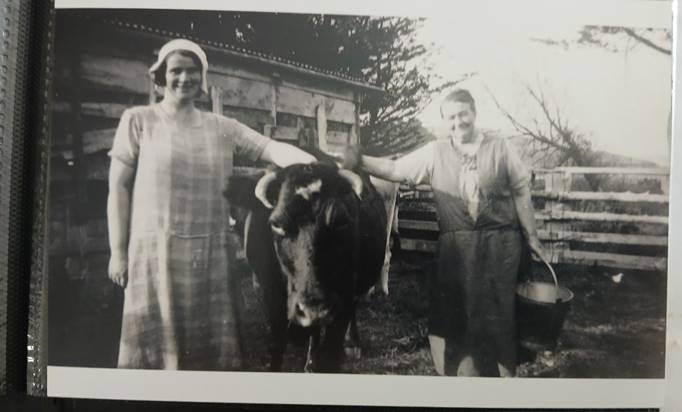

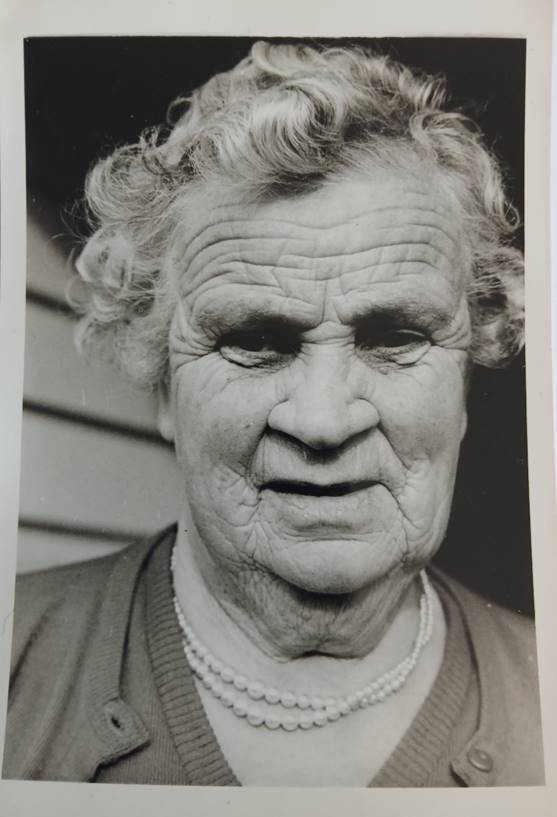

Great Aunty Bridget Kelly nee O’Grady at the Pahiatua family farm (DATE)

This is a talk I gave to the Irish Interest Group, Lower North Island of the New Zealand Genealogical Society on a very cold Saturday, 7th June 2025 at Tawa, Te Whanganui a Tara, Wellington. I refer to ‘Maureen’ and ‘you’ a few times in the recording; this was my fellow speaker, who presented just before me.

In 2016 Christopher Van Der Krogt wrote, ‘In an influential 1990 study of the Irish in New Zealand, Donald Haman Akenson noted exceptionally high rates of delinquency among Irish-Catholic immigrants in the 1880s. The Irish-born made up only 8.9% of the population but 27.0% of convicted prisoners in 1886. At the same time, Catholics (half of whom were Irish-born immigrants) amounted to only 14.0% of the colony’s population but 34.4% of prisoners convicted that year.’ (p.90)

‘Delinquency’ in this context refers to deviance from accepted societal norms, which could result in institutionalisation in asylums, reformatory institutions, reform schools or prisons. It has been said by Elizabeth Malcolm that ‘wherever the Irish went their propensity to be committed to psychiatric institutions became notorious’ (p.91).

Van der Krogt argues that five factors seem to come into play for the Irish-Catholic community and their ‘deviance’:

- Disengagement from the Church

- Being an unskilled or semi-skilled labourer

- Being single and a drinker

- Poorly integrated into the new society

- Being type-cast[1]

My Great Great Uncle James O’Grady was indeed a single Irish-Catholic who was considered deviant enough to be incarcerated in first the Auckland and then Porirua asylums, from 1903 until his death in 1942 (strangely, his grave says he died in 1949, and I’ll come to that in the challenges of our research). However he doesn’t seem to fit many of the factors Van der Krogt describes, and may simply have been genuinely mentally ill. James and his family were regular church goers, he lived in a supportive family environment. He was single, but no evidence has come to light of him being an excessive drinker. The family seems to have been integrated into their close-knit community of small farm lease holders, and it’s not evident that he was typecast.

Perhaps Sean Brosnahan’s talk last year to this group offers us further insight into James’ situation – he was born not long after the famine, his father died young and was a shoemaker, so presumably the family were not wealthy, they were assisted immigrants coming out to Napier in 1884. Perhaps intergenerational trauma was indeed part of his legacy.

It is very difficult from our perspective today to understand the emotional, psychological or even sometimes physical truths of people who lived one hundred years ago, since we may have very little written or documentary evidence, and what we have will have been created from a perspective we may not even understand. For example, I grew up agnostic, and so the role of the spiritual or supernatural realm, so important to many people today and perhaps more so in the past, in a world where mental health was often understood to be affected by the spiritual world, is quite hard for me to understand. It’s often an accusation made against people looking into the past, that we judge from our own time and lens. But of course we do, so we must just say so up front. I can only speak from my perspective today.

Some recent authors have provided thoughtful insights into mental health and the societal context of the past, during the time James was considered ‘deviant’. In Jacqueline Leckie’s new book Old Black Cloud: A Cultural History of Mental Depression in Aotearoa New Zealand [2] for example, she describes Dr T.G. Gray, the incoming Director-General of the (New Zealand) Mental Hospitals Department, who was arriving from Scotland in 1911. He noted the ‘singularly isolated position which the mental hospitals occupied in the public life of the country … their drab and dreary structure and routine symbolised the hopelessly pessimistic attitude of the public towards the prognosis of those who had to be admitted’.[3] I would add to that the pessimistic attitude of many of the staff who worked with those patients too, including that of Dr Gray himself, and we will return to him.

Jacqueline Leckie’s historical analysis begins 60 years before Gray’s observations, and her work offers a foundational history of (largely) state-based asylum care over the next century and more. While politicians wring their hands today as they discuss the new reports tabled in pParliament from the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care, rhetorically asking how abuse in state institutions could possibly have happened, Leckie demonstrates how, almost from its inception, the state system designed to support those in mental distress was vulnerable to the vagaries, fashions and dispositions of those in charge, and the ‘hopelessly pessimistic’ attitudes of the general public (and I would argue) some politicians, and even public health professionals to issues of mental health.[4] [5]

Alexander McKinnon’s family history, Come Back to Mona Vale, offers a companion piece to Leckie’s work, a detailed case study to complement her overview. McKinnon’s grandfather, Tracy Gough, was a successful Canterbury businessman who was also the purveyor of an early electric shock treatment machine. Electric shock treatment was used on his own daughter in a private hospital after an older sibling had died of an overdose of cardiazol and repeated high doses of paraldehyde, both administered at Christchurch’s Sunnyside Hospital in 1941. Chillingly, paraldehyde and unmodified electric shock treatment both featured in the (now officially acknowledged) torture of young people at Lake Alice, near Marton, in the 1970s, as outlined in one of the Abuse in Care reports.[6] One of the reasons why I’m interested in history is because I have the perennial hope that we may actually learn from the past – but the evidence suggests otherwise.

So if you’re interested in learning more about the state of asylums in Aotearoa New Zealand in the 1800s and early to mid- 1900s, both Jacqueline Leckie’s broad and comprehensive analysis and Alexander McKinnon’s more focussed family story provide excellent insight.

The other great source of information on general attitudes to difference in the early twentieth century is covered in Oliver Sutherland’s wonderful book about his father Ivan, Paikea: The Life of I.L.G.Sutherland.[7] Ivan was a philosophy and psychology lecturer who argued against the fashionable eugenics movement, which advocated sterilisation of children and adults who displayed various differences from the understood norm of the time, and also pushed for permanent segregation of ‘mental defectives’, which was essentially what happened in the series of government asylums around the country. In fact Dr Theodore Gray, who became Inspector-General of Mental Hospitals in 1924 was a psychiatrist who advocated for a eugenics board which could make decisions about sterilisation – including of children of ‘defectives’. He insisted on excluding psychologists from the eugenics board on the basis that they had nothing to offer, and his recommendations were indeed part of the Mental Defectives Amendment Bill 1928 (pp. 138, 139).

Oliver Sutherland has been very involved in the abuse in care issues of the 1970s to 1990s, and was a key witness at the Royal Commission Hearings. In the subsequent reports of the Royal Commission on Abuse in Care, we are able to see much about the treatment of those in state care including asylums in more recent times, since the report covers the 1950s to 1990s period (though they did allow testimony outside that, including my Great Great Uncle’s story). But the reports also refer to earlier treatment of patients, and we can see how many unmarked graves for example remain at former asylum sites around the country in those reports, including Porirua which is my focus today –

The Inquiry has not only received evidence of people dying in care but also of people in care being buried in unmarked graves. Tokanui (which Maureen has covered) at Te Awamutu, Sunnyside Ōtautahi Christchurch, Cherry Farm and Seacliff Ōtepoti Dunedin, Sydenham Cemetery includes Sunnyside patients, Westland Hokitika (Seaview) – not all hold sufficient records to conduct a search and confidently say where unmarked graves lie or who is in them.

Porirua Cemetery is the exception rather than the rule in the Inquiry. At Porirua Cemetery, a public cemetery, there are 2,046 unmarked graves identified in total. One thousand, eight hundred and forty of these are for Porirua Hospital patients. Porirua City Council also identified 847 unmarked graves at Whenua Tapu Cemetery and 25 at Pauatahanui Burial Grounds.[134]

I would like to acknowledge the work of Daniel Chrisp, Cemeteries Manager at Porirua City Council who has done much of the work to cross check records and create lists which are now available to the public. He is working towards a memorial for those in unmarked graves, and wants descendants to help decide what form the memorial will take.

Before reading the reports from the Commission, I had no idea how common it was for relatives not to claim their family members when they died at the asylums. James’ body was brought home at his death. Some commentators state that families were uncaring when it came to mentally ill family members, but the societal pressure to conform, and the shame of having a family member incarcerated was very real and serious during the time period my Uncle was in the asylums, but according to Hilary Stace, families often weren’t told when a patient was moved due to lack of beds in an institution, and they weren’t always notified when someone died.[8] Daniel Chrisp told me you could have a patient from Christchurch, and there if there weren’t enough beds there and they’d just move them to Auckland because it was more convenient for the hospital. I would surmise Irish immigrants were wanting to fit in tended to keep their head down and conform within their own parameters, and, like other families were not encouraged to visit their family members in the asylums. I imagine some did not have the means – my immediate Kelly family for example didn’t get a car until the 1950s, so travelling out of town to an asylum would have been challenging, as they were often deliberately not put on public transport routes according to another excellent book Wendy Hunter Williams, Out of Mind Out of Sight: The Story of Porirua Hospital, Porirua Hospital, Wellington, 1987 – even though it’s older, I would recommend it.

The other thing I would say is it can be frightening to have a mentally ill family member, and you may just believe that the best thing you can do is keep away. In my Uncle’s file it says he held his brother in law William up by the neck and threatened to kill William’s wife, my Uncle’s sister Bridget (that’s Bridget with the chooks) and their Mum, Brigid O’Grady. I can understand why they might not go to see him after that, and they would not have had any understanding of mental illness in 1903. They may even have believed the devil had taken him.

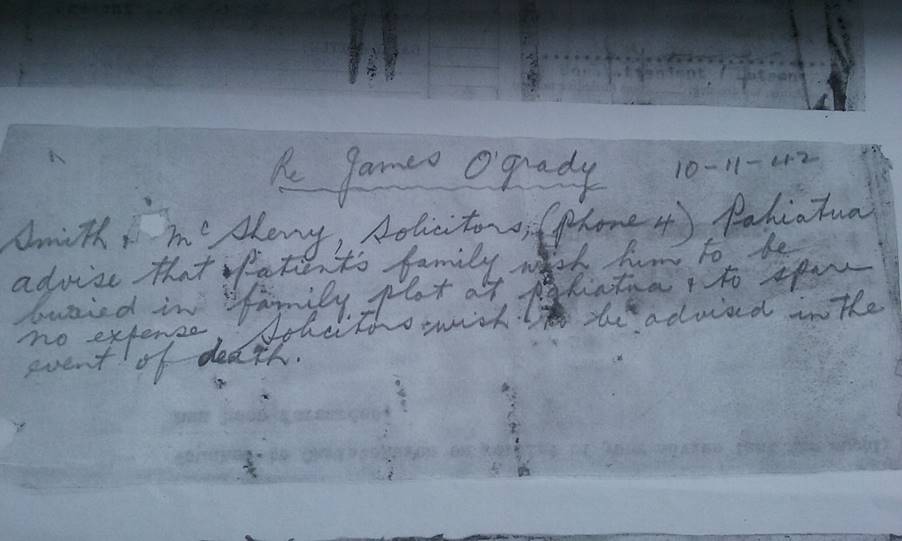

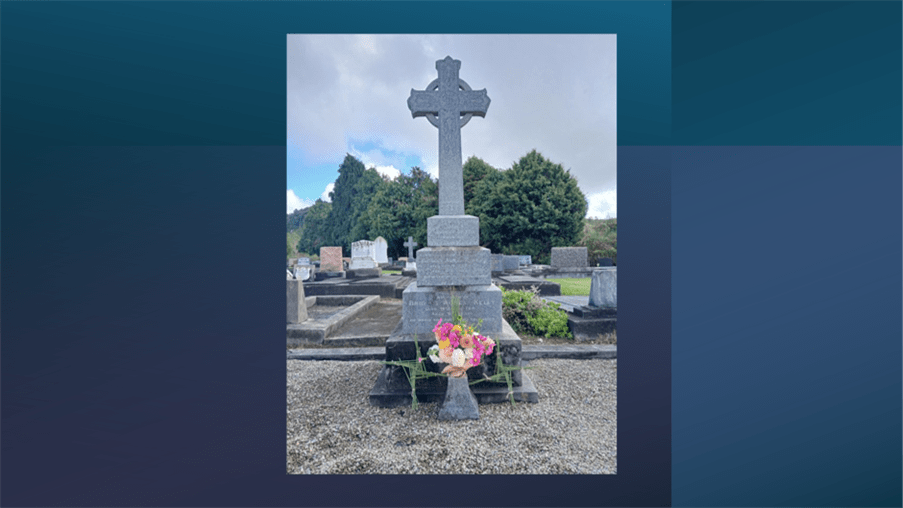

So when my Great Great Uncle James died, his family, my family, the next generation from those who incarcerated him, sent a telegram to the institution urging them to ‘spare no expense’ in sending his body home, and he indeed lies in the family grave with his sister, mother and brother in law at Mangatainoka (image).

I don’t even know if Lizzie Kelly and her husband Colin who sent this letter had ever met James. This is from James’ CCDHB file. It’s extraordinary, with the original letter from his doctor explaining why he is being put in the asylum, describing his behavior in the asylums, and then from the time he is moved to Porirua, what he does there – he works on the farm, with the pigs who receive national awards, he doesn’t speak much. The entries become very repetitive, just one or two lines over the years, it’s very sad to see how these busy staff didn’t have time to sit with patients (in fact, nurses could be told off for sitting with patients as that was considered shirking their real work, such as polishing the floor). I have written a whole article on this file, which is freely available online, called ‘The Disappearance of James O’Grady’. So that’s James’ end, but what was his beginning? How did our family find out about this relative we had never heard of? It all started, as these things often do, with an Aunty who wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.

Bridget O’Grady’s travelling trunk came into my possession in the summer of 2017. It came from an early twentieth-century farmhouse at the intersection of Pongaroa and Middle roads, near Pāhiatua in the Tararua region. The current owner of the farm, Graeme Vial, had a chance encounter with my Aunt Carole, who was visiting Aotearoa for the first time in 40 years from her home in South Africa. She walked around the farm, telling Vial stories based on her childhood memories. She recalled riding horses and helping out around the farm, and told him where various farm activities had occurred.

At the end of their meeting, Vial decided to show Carole a series of photos that had been left at the house by the previous owners, members of our extended family. He also offered to give a trunk from the old farmhouse to the family member who lived nearest to the property: me.

My great-great uncle William Kelly married Bridget Agnes O’Grady in 1891, and was the first of the Kelly side of my family to move to New Zealand. When she was about 20, William’s niece Lizzie moved from Ireland to Pāhiatua to help on the farm after William died in 1922 – she moved in 1923, a significant year for Ireland – the end of the Civil War. Lizzie became a farmer, and eventually married the boy down the road, Colin Dron, uniting two farms and two families – and more recently we’ve learned that Dron is a Scottish name, but Colin’s Mum was a Larsen (or originally Larsson from Norway; her grandfather was one of many Scandinavians to come to the area to clear the 70 mile and 40 mile bush). I’ve also learned from Celine Kearney’s Southern Celts: Stories From People of Irish and Scottish Descent in Aotearoa, Mary Egan Publishing 2023 p.38, that back in Scotland, it was common for Norwegians and Scots to marry (geographically it makes more sense!).

My Aunt Maureen, my father John and their younger siblings Mike and Carole told their children stories about the Pāhiatua farm in the time Lizzie and Colin ran it, and the photos help bring the story to life. As children they had visited in the holidays; it was a stable place in a changing world which included the second world war, which started three years after my father was born, with all the rationing and other difficulties it entailed for those who stayed home. There are some wonderful descriptions in letters from my grandmother Jean to my grandfather Jack about the milk, cream, tomatoes, and other fruit and vegetables she brought home from the Pahiatua farm in a time of austerity. (family blog photo)

So I’m showing you here photos from the family blog I’ve started to share these stories and memories as my Irish diaspora family live across the world, from South Africa to London to Australia and New Zealand (we are true colonials scattered across the Empire). My Dad, Aunty and Uncle who are kids in these photos are now in their eighties, and it’s important to me as the next generation to accurately record their stories before they pass away.

My grandad (my Dad’s Dad) Jack worked on the railways, and although that meant they lived in railway houses so had security of housing, they moved on the whims of the bosses – Christchurch, Petone, Frankton Junction, Ngaio and Taumarunui – during their childhoods. So the stories of the farm were precious memories or holidays and freedom and fun. Uncle Michael has recently talked about driving a tractor called Fergie at the farm; Dad remembered riding a horse which suddenly refused to cross a bridge; and Aunty Lizzie was a favourite relative of both my father and my mother. In our house in Auckland there were photos of Mum and Dad with Aunty Lizzie at the farm when my parents first married in the late 1960s. As kids we were fascinated by photos of her and her huge bosom and deeply lined and wrinkled face.

Back in 2017 my friend Ed and I drove from Wellington to Pāhiatua to meet Graeme Vial and his partner and pick up the travelling trunk connected to an extended family I had heard about but never met. When I initially saw the trunk I felt disappointed, as it had a broken lid and was empty. Nevertheless, Ed and I put it in the car and then sat down for a cup of tea with the people who had kept it for all those years. Our host Graeme’s previous partner was Ngāi Tahu. Before she died, she had been the keeper of whānau, hapū and wider iwi stories, ngā kōrero tuku iho we call them. From her, Graeme, who is Pākehā, had learned to understand the importance of ngā taonga tuku iho, treasured things passed down. For this reason, he had kept the photos and the trunk in the hope that one day the family of the previous owners of the farmhouse would be ready to take on these treasures.

He also kept them because of his own unusual inheritance. When my Great Aunty Lizzie (née Kelly) and then twenty years later her husband Colin Dron, the owners of the farm, died, they left the property to Graeme’s parents, because they had helped Colin keep going as he grew older. Graeme remembers, as a teenager allergic to cow’s milk, being given the job of milking Colin’s animals when he was unwell – and the skin complaint that was the inevitable consequence. During a recent visit to the wonderful Pahiatua Museum, locals told us that Graeme’s Mum would make a meal for my Great Uncle Colin every night after his wife Lizzie died. I feel glad the family that helped Colin and Lizzie received a reward for their many years of effort and support.

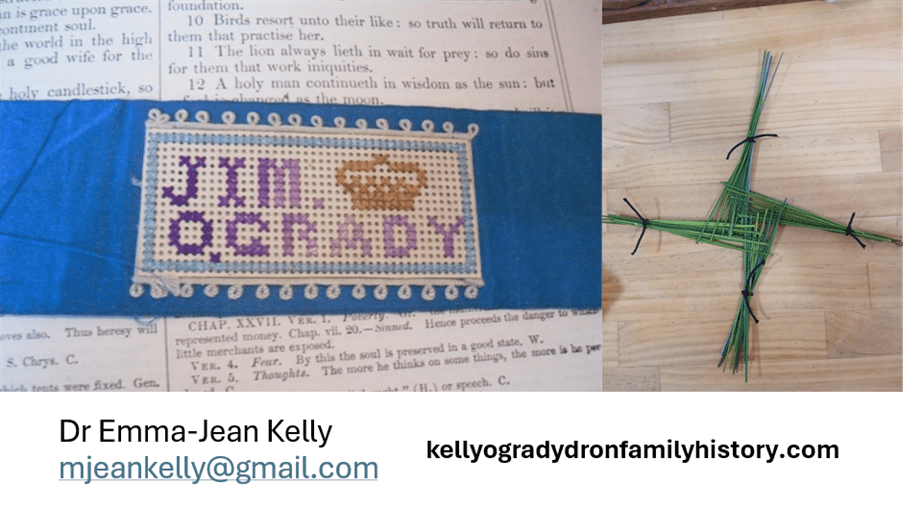

Back home after our trip to Pāhiatua, I reassembled the pieces of the trunk. As I did so, I noticed that inside on the bottom boards, written in pencil in a child’s hand, was the name ‘James’. (Image on slide)

Who was James and how did he fit into the family? No one in my immediate family knew.

But suddenly things in our family house, like this embroidery in the huge old Catholic family bible, made a little more sense:

Like many other Pākehā families, we do not reflect on the journeys of our ancestors, nor do we tell our children about them. But the older we have become, the more we have begun to talk. This is particularly so at funerals and in times of crisis, such as family members becoming ill; stories have been shared, and so slowly I have learned about our family’s origins.

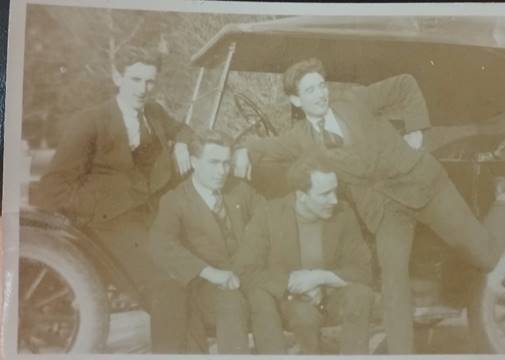

The stories of my paternal family have always been dominated by the legend of my grandfather who fought in the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on the Anti Treaty side during the Civil War. Jack Kelly, my Dad’s father, was born in 1898. Jack, like so many young men across the Empire, lied about his age and signed up to fight for the British in the First World War. I have since read that about 210,000 Irish signed up to fight and often they were seduced by propaganda about their own martial status as coming from a proud warrior legacy, similar to rhetoric about Māori who signed up for the Battalions.[9] Similarly to Māori they believed that fighting for the British would once and for all give them full citizen rights in their own country. This did not happen for either the Māori or the Irish without a fight. It’s also argued that Catholics signed up to support other Catholics attacked in Belgium and France – so some argue it wasn’t about nationality but religion. Portarlington, originally called Cooletoodra is on the border between County Offaly and County Laoise. It’s just over 70 kilometres west of Dublin. Jack’s parents, John and Mary, ran a successful bakery at Portarlington and apparently spoke fluent Gaelic, and had many children, not all of whom survived to adulthood. We have letters from childhood friends of my grandfather, reminiscing about the ‘good old apple pies’ Jack’s mother used to share out among the kids in the neighbourhood.[10]

Through the family blog, we have been able to communicate directly with County Laoise historian Michael Rafter who has written a book about the Civil War activities in my Grandfather’s area, and in fact we’ve found Jack in Michael’s book. There was also a misnamed photograph of Grandad in his anti-treaty IRA outfit on an official website dedicated to the Tondoff Ambush Grandad was involved in. The photo was miscredited originally in Michael Rafter’s book.

Not only has the website now been amended to name Grandad (even though this is a reluctant admission on our part) we have also got a copy of Michael’s amazing book which is set for a reprint called The Quiet County: Towards a History of the Laois Brigade I.R.A. and Revolutionary Activity in the County 1913-1923, Michael J. Rafter, 2016. In fact the first person I contacted about the misnamed photograph is the curator of the website, who is descended from one of the men who was killed during the ambush my Grandad was involved in. He was very gracious given my family’s involvement in that death.

It’s been amazing to connect with Michael, who has been able to identify people in photos we had, as fellow members of Jack’s battalion of the IRA.

Jack Kelly was apparently a man of few words in Irish or English. He did not talk about the First World War or the Irish Civil War, or even very frequently about his family back home. My Dad says they did not discuss politics at home, although Jack did give his eldest son the middle name ‘Eamon’, for the Irish political leader, Éamon de Valera.[11] They also had a picture of Mickey Savage on the wall, which was common for working class families of the time. My uncle Mike, Jack’s youngest son, was told, probably like every Irish diaspora visitor before him, that when de Valera visited Portalington he had been offered safe refuge in the Kelly household when he was on the run. We cannot prove that this is true, but we have documentary evidence, and more now from Michael Rafter that Jack was an IRA man and ran his battalion from Portalington. This information originally came from a military historian based in Ireland, hired by my uncle Mike. Released from jail at the end of the Civil War, Jack moved to New Zealand in 1926, married a Scottish Protestant New Zealander, Jean Rodger Martin, and had four children. He worked for New Zealand Railways as an electrician for the rest of his life. This was all I knew about my paternal family.

The farm my Great Great Uncle William (so my Grandad Jack’s Uncle) and Bridget Kelly settled on was part of the Mangahao Survey District, Block VIII (or XVIII, depending on the file), and was called the Pahiatua Special Village Settlement. It was subject to a 999-year lease from her Majesty the Queen, dated 1 July 1886.[12] And so my Irish family, who knew all about occupation, the oppression of their culture and language, lived on Māori land, leased by the Crown and given to settlers to develop. I have no idea what they thought about this, or even if they thought about it at all. When my grandfather Jack sang ‘Galway Bay’, a popular song of protest against English occupation to his New Zealand-born children, did he do so with any sense of irony?[13] Dad just told me that ‘The Wearing of the Green’ was also sung a lot at home.

Graeme Vial and my father John began an email correspondence around 2017, and Graeme asked: ‘How were the Kelly and O’Grady families connected? Colin [Dron, Lizzie’s husband] used to mention the name, and the section over the road from the house is still known as Jim’s section, named after Jim O’Grady.’[14] At the time my father was unable to answer this question, having no knowledge of Jim’s migration to New Zealand. (So that travelling trunk for Brigid O’Grady, so far as we knew, was hers alone – we thought she was a single Irish woman in her twenties who came out to go into service, as so many did. We didn’t know about the children she’d brought with her, one of whom had her name). Our cousins the McGreevys whose mother Pat and siblings also visited the farm as children knew nothing else about Jim except that he lived his life at Porirua Hospital and was buried in the family grave, which my cousins Gerard and Stephanie have maintained.[15]

And they only thought to tell us this because I happened to have the travelling trunk with me when we visited and I mentioned the name ‘James’ written in the bottom. My cousin Gerard said ‘oh poor James’ and his knowledge of the story came out for the first time.

This was where my research skills came in. It took me a while, but I was able to apply to the CCDHB – Capital Coast DHB to get permission to access James’ files held at Archives NZ. They are the most fulsome account we have of James. And if you’re interested in applying for one of these files, I’ve written a short piece on the family blog about the process, I can show you at the end. It’s a little longwinded, the process, not the piece.

If you haven’t been to the Porirua Hospital Museum, I highly recommend it. It’s creepy and terrible, and also very educational. It is an original ward from the hospital. Keep in mind though, that there are still mental health wards at what is now called Keneperu. It’s still a place of challenge and tension and suffering for many. And the unmarked graves are just over the hill at the cemetery on the same site.

In continuing to look at block files at Archives NZ I was able to work out that actually it was not my Great Great Uncle William Kelly who purchased the lease on the farm at Pahiatua – it was his mother-in-law, Brigid O’Grady, widow of a shoemaker, who with her 2 children in 1884 had come to New Zealand with that travelling trunk, and after a few years was able to purchase the first of two family leaseholds in the Pahiatua Special Settlement Village. James, who four years later was incarcerated in the asylum, managed to purchase the leasehold for the second section over the road in 1899, having previously had 100 acres at Mt Cerberus, which was an area along the road towards Hawkes Bay north east of Pahiatua (I went down a rabbit hole at Archives with this one, as today Mt Cerberus is in the south of the South Island). The records which can seem dry at times were another revelation to me when I realised James had been considered capable of running a farm prior to being put in the asylum and I could see his signature and handwriting on various legal documents for the first time. Once he’s in the asylum, he has no written records of his own. Furthermore, the Archives NZ files revealed that three generations of Irish Women in my family owned and ran that farm – Brigid passed both leases (because 13 years after he was put in the asylum, his mother was able to take over James’ lease) to Bridget her daughter who married my Great Great Uncle William, and Bridget left the farm in such a way that Lizzie, William’s niece, was eventually able to purchase it (though that’s a whole story). We had assumed the men in the family had owned the leases. Why? We just did.

We still have some questions about James and some of our other family stories – we haven’t yet worked out when William arrived in NZ because ‘William Kelly’ is such a common name and he doesn’t seem to have had a middle name to distinguish him. The Scottish side are much easier to identify because the women generally were given a middle name which was their mother’s maiden name. I wish the Irish had done the same! We’ve never found a photo of James, but I hope to one day. I hope to do some more research about the O’Gradys – one of my Grandmother Jean’s letters mentions that Aunty Bridget O’Grady told her she came from the same area as Jean’s friend the English family (somewhere in Tipperary, that’s all we know at this point).

This group, Irish Special Interest family historians, has helped me find new tools I had no idea about to research my family history, and talking and listening to you all has helped me bring it to life – the good and the bad of it. Like many people, there has been tension at times in sharing these stories with family who may not want to know some of the detail about madness, or the neglect of unwell family members, or who grew up with a different version of a story to that which I’ve found. Nevertheless, it has been a great process for my family to talk through the past and what it means to us, and to talk about colonisation and our role in it, particularly as my father is now 88, and finally in the mood to reflect on his life and the life of our family a little more.

We’re lucky to have a family grave to visit, and that James is resting there, even if it says he died in 1949 when his hospital file says it was 1942.

And family photos to share – my Dad is a keen photographer and is particularly fond of this one he took of his Aunty Lizzie in old age, though she may not have liked it so much!

What I have learned, is that even if you think you don’t have information in your family, you do, it just may take a while to work out what it means, to uncover its value, to see the child’s scrawl on the bottom of the trunk, or understand the keepsakes in the family bible. And the only way to do that is to ask, and research, and share and listen. Thank you.

Appendix Royal Commission further information on unmarked graves

95. The Inquiry received some information on unmarked graves at Tokanui Psychiatric Hospital located south of Te Awamutu, Sunnyside Hospital in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Cherry Farm in Ōtepoti Dunedin, Seacliff in Ōtepoti Dunedin, and Porirua Hospital. Evidence was provided by Mr Wright and his team, who have identified 765 Sunnyside patients buried at Sydenham Cemetery between the years of 1896 to 1934 (the most recent year transcribed to date).[131] Mr Wright predicts there could be upwards of 1,000 Sunnyside patients at Sydenham Cemetery, with the majority of these being unmarked.[132]

96. At Tokanui Hospital Cemetery, work undertaken by Anna Purgar has verified 469 people as being buried in unmarked graves. Several bodies have since been exhumed and reburied in other cemeteries.[133]

98. The Westland District Council had not done any research into unmarked graves at Hokitika Cemetery and stated that it does not hold sufficient records to conduct a search. Despite this, the Council was able to provide this Inquiry with the names and plot numbers of 83 individuals buried in Hokitika Cemetery, with the last known address recorded as ‘Seaview Hospital’ and without a headstone recorded on the Council’s records. However, the Council notes that the records “may not accurately reflect what is actually on the ground,” meaning they do not know for sure which graves are unmarked.[135]

99. In 2014, a local historian identified 172 unmarked graves at Waitati Cemetery, Otago. About 85 percent of these graves are from former institutions such as Cherry Farm and Seacliff. The historian noted that the last burial was in 1983, with many in the 1930s and 1940s.[136]

Note 134 – Porirua City Council, Letter, Response to Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care Notice to Produce 487 (29 July 2022). Note: Porirua City Council calculated the “number of unmarked deceased, which will be slightly different to the number of unmarked graves as many graves will have multiple deceased buried in them, this was a more accurate way for us to report”.[16]

[1] Christopher J. Van Der Krogt, Irish Catholicism, Criminality and Mental Illness in New Zealand from the 1870s to the 1930s New Zealand Journal of History, 50, 2, Massey University, (2016).

[2] Massey University Press, Auckland, 2024

[3] Alexander McKinnon, Come Back to Mona Vale: Life and Death in a Christchurch Mansion, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2021, p. 281.

[4] Oliver Sutherland, Paikea, the story of I Sutherland, (details)

[5] That Leckie’s history of mental depression was published in the same year as the final report of the years-long Royal Commission feels appropriate. It helps us contextualise the long history of isolation which has at times characterised institutional care in this country. But it also offers ‘glimpses of the lives of those admitted to’ those institutions, as well as the attitudes of those who administered and managed them, as Barbara Brookes has argued in relation to paperwork from the files of Seacliff Asylum.

[6] Beautiful Children, Te Uiui o te Manga Tamariki me te Rangatahi ki Lake Alice | Inquiry into the Lake Alice Child and Adolescent Unit, December 2022, New Zealand Government.

[7] Canterbury University Press, 2013.

[8] For an excellent examination of ‘Shame and its Histories in the Twentieth Century’ refer to Barbara Brookes’ article of that name in Journal of NZ Studies, Antipodes New Directions in History and Culture Aotearoa New Zealand, No.9 (2010).

[9] Heather Jones and Edward Madigan, Chapter 5 The Isle of Saints and Soldiers: The Evolving Image of the Irish Combatant, 1914-1918 in Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2019, DOI:10.1163/9789004393547_007

[10] Letter of Tommy Cribbins to Lizzie Kelly (date?) John Kelly’s archive, Auckland.

[11] John Kelly recalls that within the family it was said Jack wanted ‘Éamon’ as John’s first name, but his wife Jean was concerned other children would tease him at school by calling him ‘Amen’. John Kelly to author, 20 July 2018.

[12] Certificate of Title Under Land Transfer Act, Leasehold No 6a/261, Lessor Her Majesty the Queen under Part III of The Land Act 1892, No. 534.

[13] For the breezes blowing o’er the seas from Ireland,

Are perfumed by the heather as they blow,

And the women in the uplands digging praties,

Speak a language that the strangers do not know.

Yet the strangers came and tried to teach us their ways,

And they scorned us just for being what we are,

But they might as well go chasin’ after moon beams,

Or light a penny candle from a star.

And if there’s gonna be a life hereafter,

And faith somehow I’m sure there’s gonna be,

I will ask my God to let me make my Heaven,

In that dear land across the Irish sea.

[14] Graeme Vial to John Kelly, 20 November 2016.

[15] Discussion with tour guide at Porirua Hospital Museum, 12 June 2018.

[16] Ngā rua kōiwi ingoa kore: Unmarked graves section, Royal Commission Abuse in Care Inquiry https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/reports/whanaketia/part-5/chapter-2#_ftn133