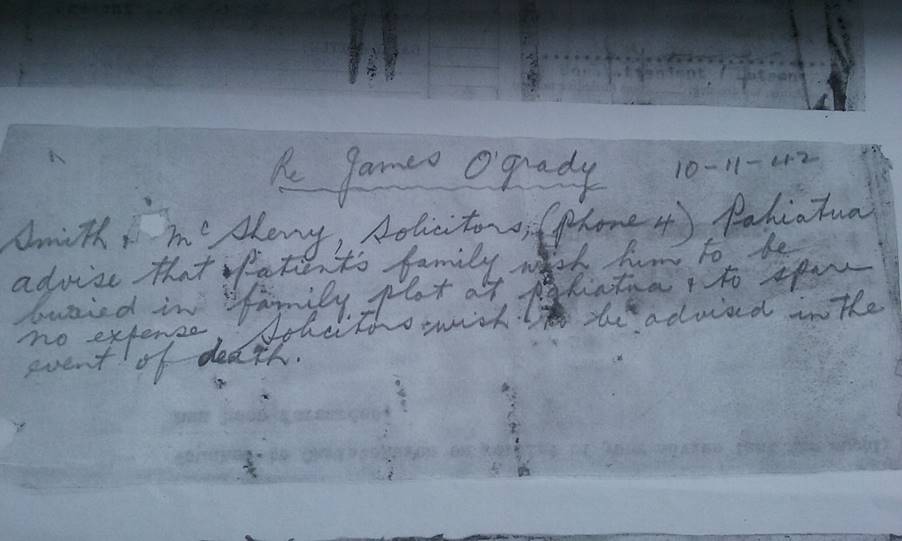

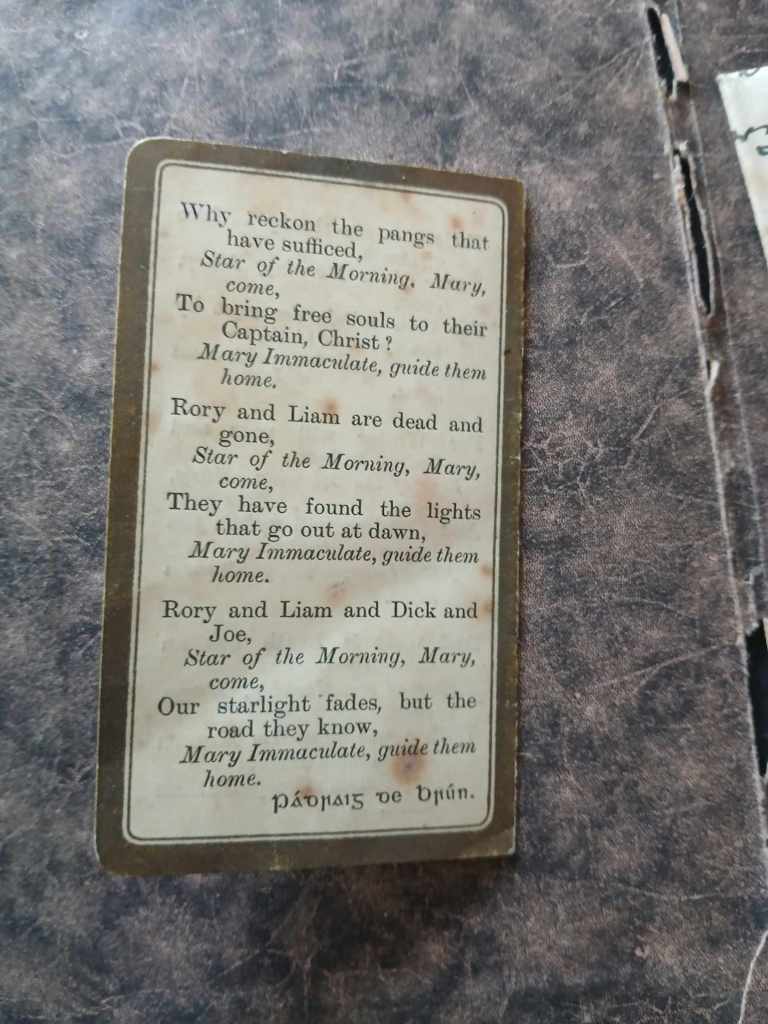

Pahīatua Holiday Memories – John Eamon Kelly

Pahīatua Recollections of John Eamon Kelly (JEK), recorded by Emma-Jean Kelly (EJK). This is an edited transcript checked by John. John had written some notes in advance about things he remembered, so occasionally Emma-Jean mentions ‘your notes’ in the interview.

Recorded on 24th December, 2025, at 51 Eskdale Rd, Birkdale, North Shore Auckland, on Zoom H6 with lapel mics. Photo below of John’s hands, putting sugar in his coffee.

Recording One of Two

EJK- Kia ora, I’m here with John Eamon Kelly, my father. My name is Emma-Jean Kelly, and we’re going to chat about Pahīatua where Dad went on his holidays as a youngster. Hello Dad. OK, you don’t want to say hello back? [laughs]

JEK- Oh, hello back [laughs].

EJK- So are you comfortable saying when you were born and where?

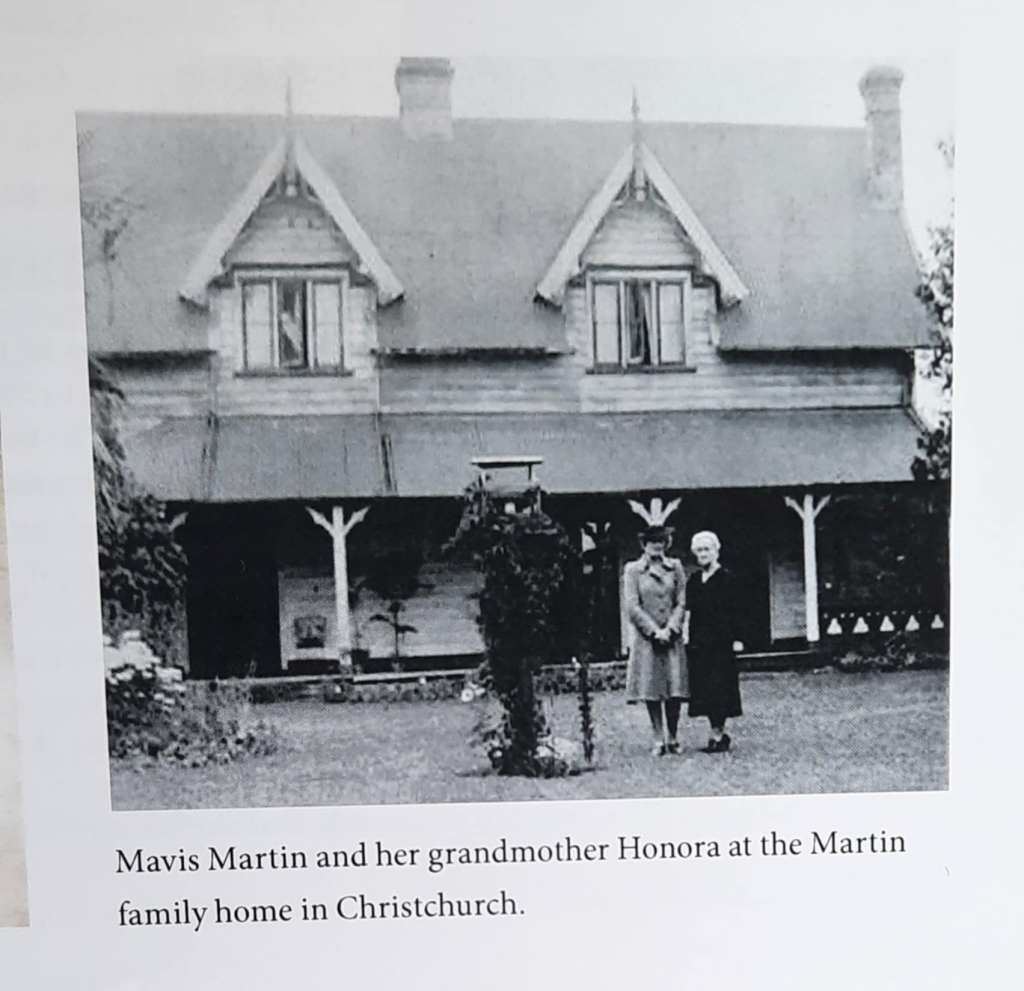

JEK- I was born in Christchurch in 1936. My mother lived in Fairfield Avenue, in a two-storey house which we have photos of but of which I have no recollection apart from one visit, one visit when I was taken there by my father when I was an early teen.

EJK- And what did your mother’s family do? What did her father do?

JEK- Mum’s father was an ironmonger, and I believe he built the big iron gates at Hagley Park. He was instrumental in doing that, or his business was, we were always told he built them.

EJK- Nice. And what cultural background was that side of the family?

JEK- I’ve no idea really, except we’ve got photos of musical events, one of my aunts Aunt Mavis, was a dancer, I don’t know who with or if it was only when she was a child. Therre were dress ups, there is a photo of all the children, my mother’s siblings in kilts

EJK- And they definitely had a Scottish background as the grandfather was involved with the Scottish Society in Christchurch I think; I’ve seen a write up in the paper when he died.

JEK- OK

EJK- And what about Grandad Jack?

JEK- What about Grandad Jack?

EJK- You mentioned he’s from Ireland. Whereabouts?

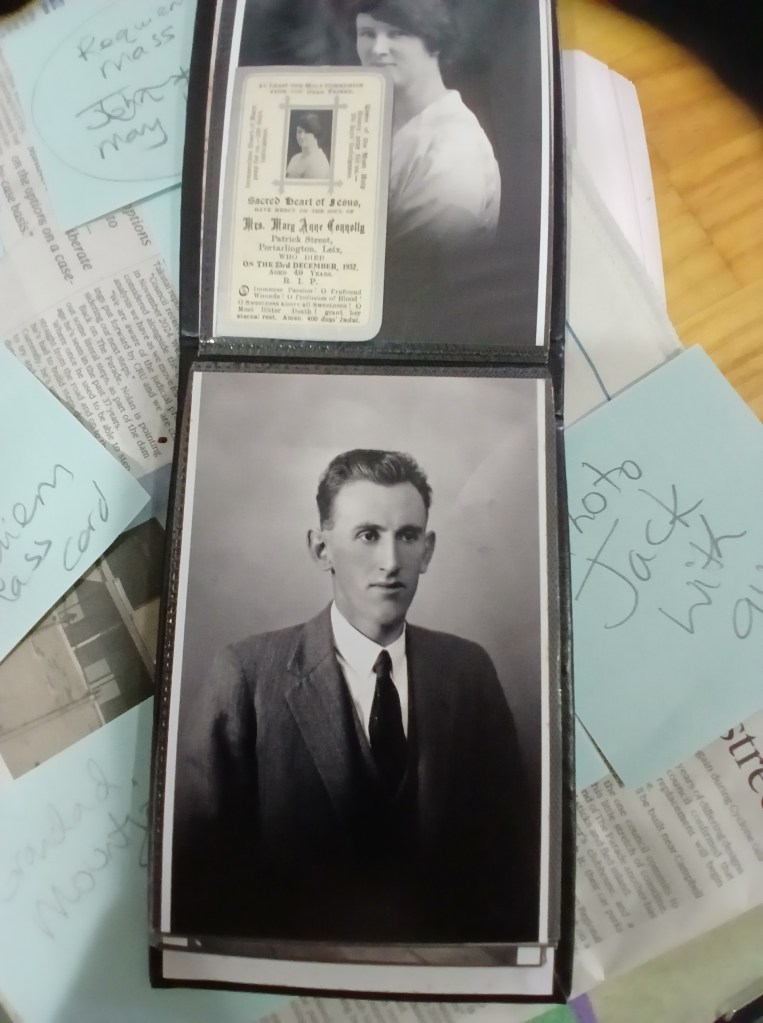

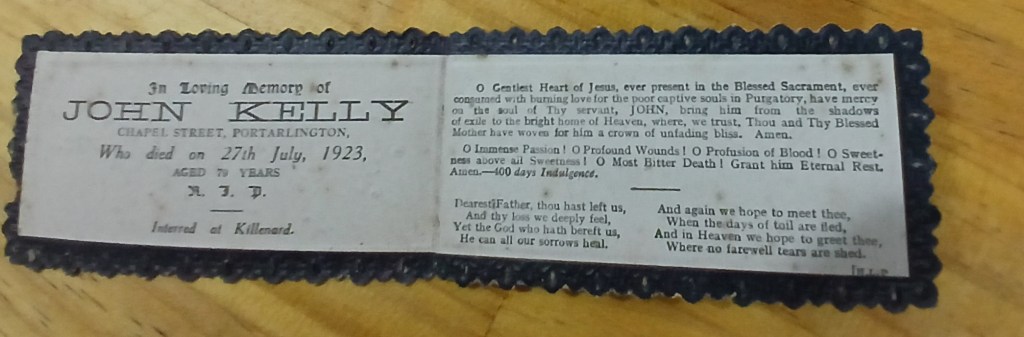

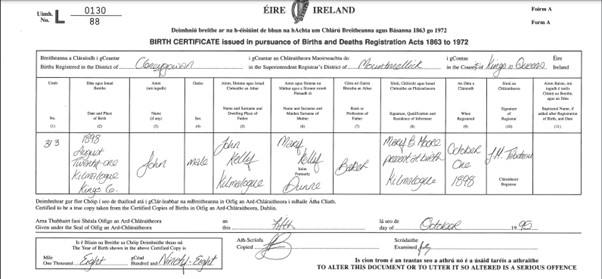

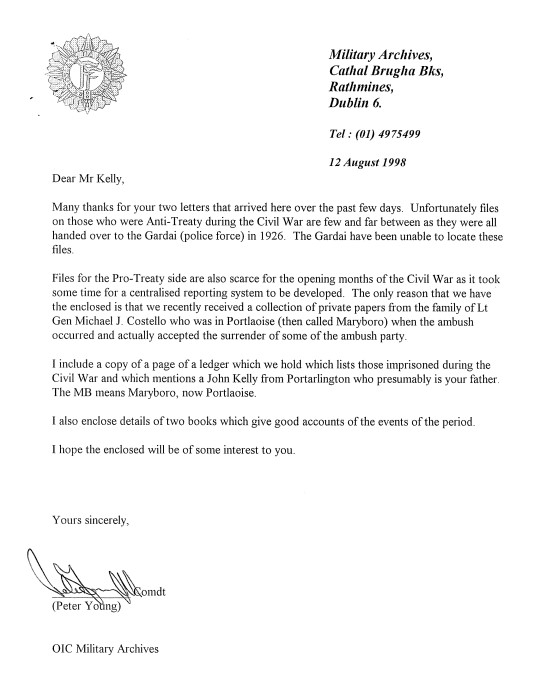

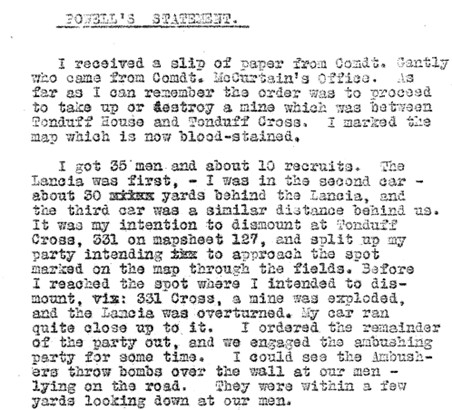

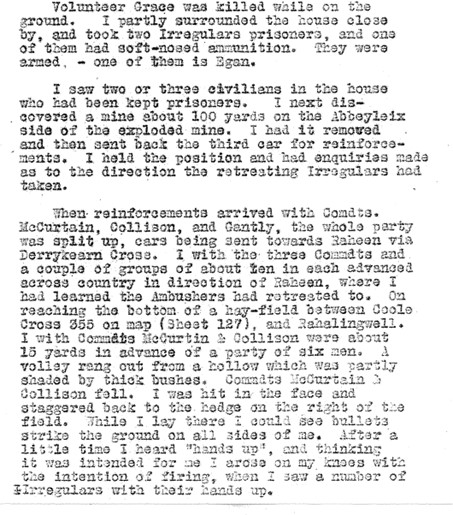

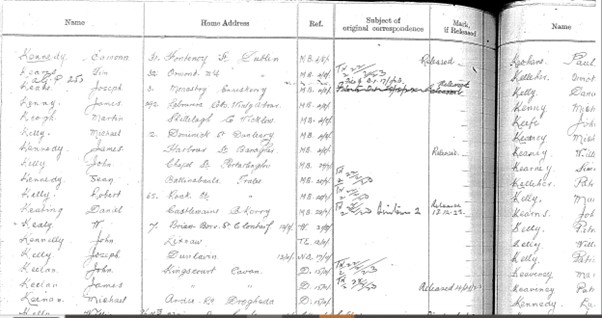

JEK- Portarlington. Which is in County Offaly, straight across from Dublin.

EJK- And he came out in 1926 on the [boat] Athenic, and we’ve still got the passenger list.

JEK- Yes

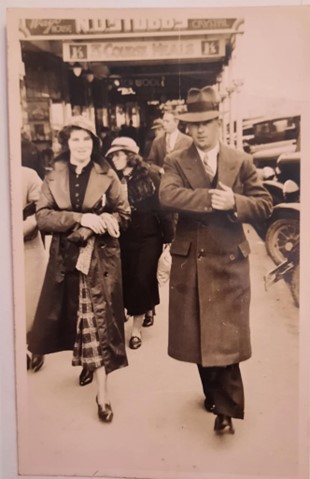

EJK- And we don’t quite know, do we, how Grandma and Grandpa met but it was in Christchurch?

JEK- Yes.

EJK- I’ve seen a letter now where she talks about slipping a note under his door

JEK- Oh!

EJK- And then they went out, but I don’t know where

JEK- Well,he was, he must have been with the Railways [New Zealand Government Railways] at that time. I presume that was his first job when he came out, with the railway, but why he was in Christchurch I’m not sure.

EJK- And they fell in love and married at Christchurch Cathedral. And who was the first born?

JEK- My sister Maureen. I remember Mum giggling and saying Maureen was born nine months to the day from their wedding night/day.

EJK- I’m trying not to giggle because I think that’s funny. And I know they flatted, well they rented a place in Christchurch, they didn’t own that place, and then you were the next born in 1936 in Christchurch. How long did you all stay there?

JEK- I believe I was 18 months old when they moved because Dad was moved by the Railway, moved to Petone in Wellington, I presume they stayed at a railway house but they could have stayed with Dad’s brother Mick and his wife Frances.

EJK- And what did Mick do for a living?

JEK- Mick was an engine driver [for the Railways]. His connection with the Railways must have been what caused my father to become a railway person.

EJK- And were there any other family members in New Zealand at the time or Grandad’s time that you know of or knew of as a child?

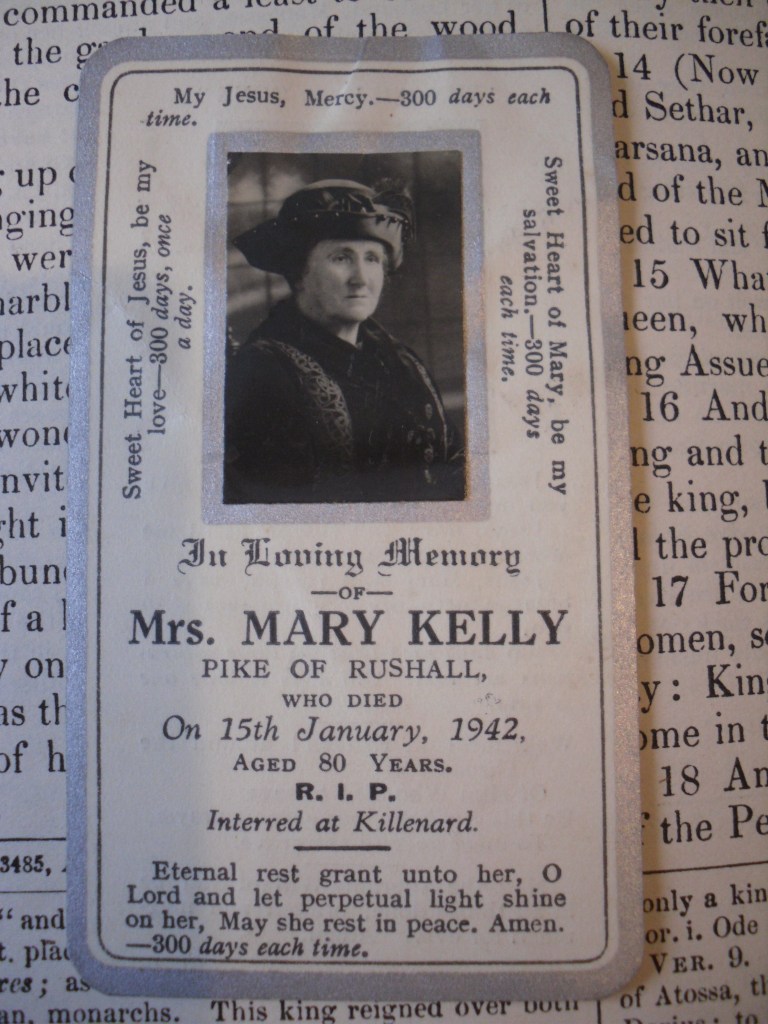

JEK- Aunty Lizzie, one of my father’s sisters must have been on the farm in Pahiatua by then.

EJK- And so that became a place for family holidays.

JEK- Yes

EJK- Do you know around about what your earliest memories are of going to the Pahīatua farm?

JEK- No, ah, I don’t, I don’t know how old I was even, but because Dad was on the Railway we had holidays in Thames, Te Puru Bay, and once we had a holiday in Bowentown past Waihi where we saw a whale, a beached whale. Because there was no road then the taxi had to drive up the beach.

EJK- Was the whale still alive?

JEK-I don’t know, the taxi didn’t stop!

EJK- So Grandad was on the Railways so you had these holidays. Did that mean you had free railway travel?

JEK- Yes,I think so

EJK- Was there a Railway bach you stayed in or did you just rent one?

JEK- Rented like other people I think, the Railway free travel just used to get us there and back

EJK- Right. And when you went to Pahīatua how did you get there?

JEK- We went by train, and my Uncle Colin, Lizzie’s husband would pick us up in Palmerston North. I don’t think the train went to Pahiatua ever when we went there. So we were always picked up by him and driven through the Mangatainoka Gorge which is now no longer a road, the road is at the back of the hills now

EJK- What did Uncle Colin drive at the time do you remember?

JEK- No, he did have a converted Model AA was it, the big car, I don’t think he drove us in that because it was the truck, we thought of it as the truck which was used for farm stuff

EJK- And that was a bit of a legend wasn’t it? Did he cut off the back of the car?

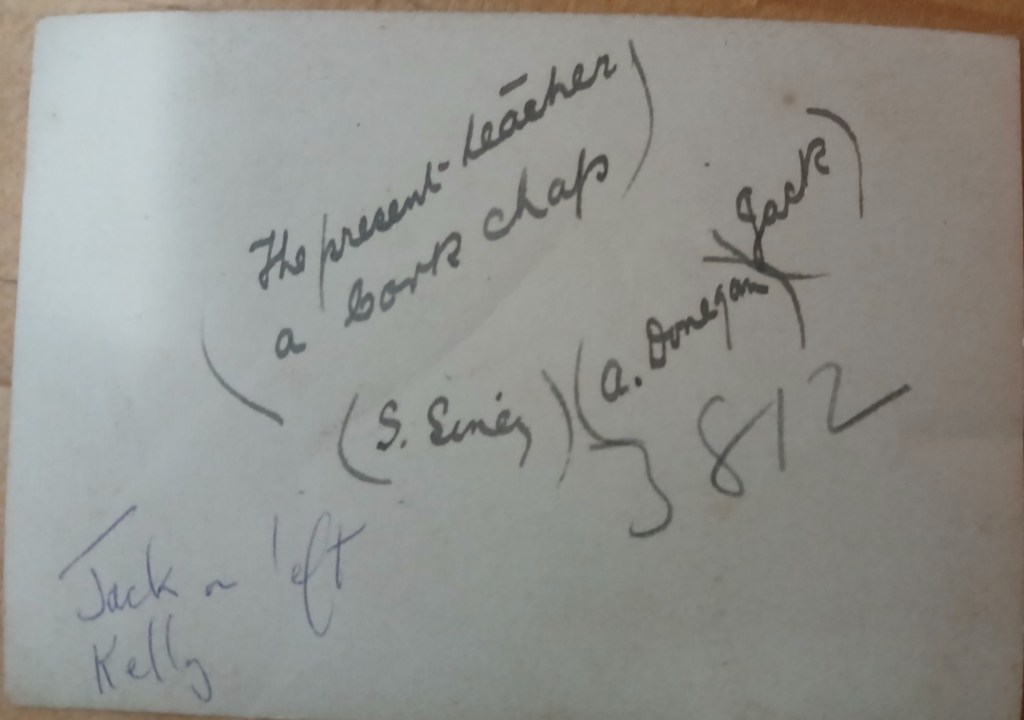

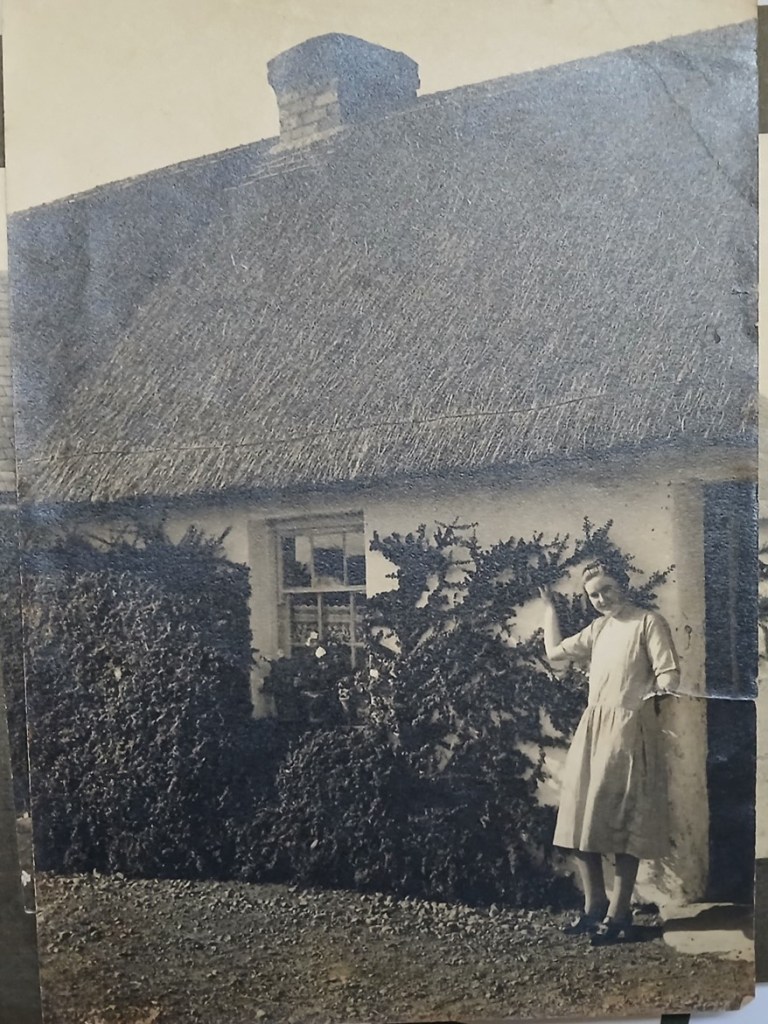

JEK- Yeah, it was a, you’ve seen photos of the car Aunty Lizzie used to drive, that was the car that was converted by taking the back off.

EJK- So that’s the car that Aunty Lizzie learned to drive in?

JEK- Well I don’t know if that was the same car, they could have changed cars over the years, but that’s the one I remember, though I can’t remember what she actually drove, what she drove us into Pahīatua in. [Dad and Emma-Jean subsequently discussed this. EJK was referring to an incident in the newspaper where Lizzie and Jack’s Aunty Bridget Kelly was accused of obtaining driving lessons from the local car dealer for her niece under false pretences (apparently she promised to buy the car after the lessons were completed but didn’t). But this was in the 1920s, so we concluded it probably was not the same car.]

EJK- So Aunty Lizzie, Grandad Jack had a lot of siblings in Ireland, was she younger? I can’t remember.

JEK- Yes, I think she was, I’m not sure. You’ll have to look at that photo there [points to the family portraits on the wall]

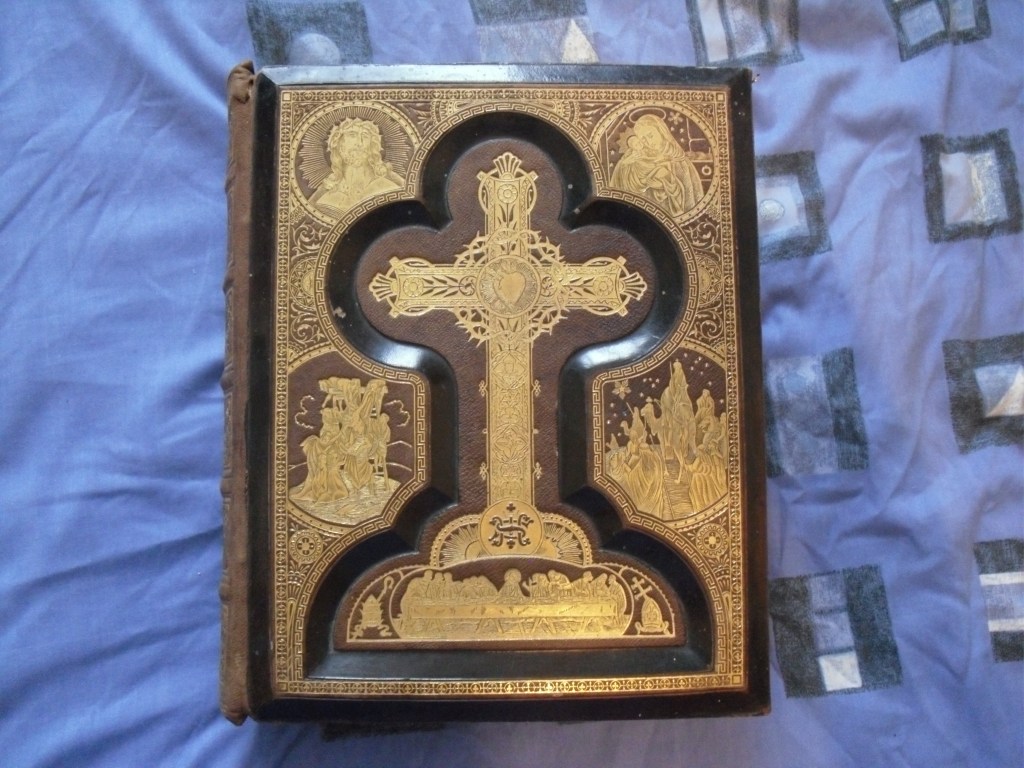

EJK- And we know she came out because the other relative that had come one generation before, or was one generation older, was Uncle William Kelly, so Grandad Jack and Lizzie’s Uncle, and Mick’s, had come out earlier and he’d married into the

Pahīatua family, hadn’t he? So we’ve got the big family bible of his wife Bridget O’Grady and they married in 1891. So he was out there on the farm, but you would never have met because he died in the ’20s.

JEK- Yes, and I’m old but not that old [laughs]

EJK- [laughs] Not that old. So you were on the farm in the next generation of the Kellys, but there had been previous generations on the farm. Did you ever hear stories about the previous generations on the farm?

JEK- No,the only connection to the farm [from the old days] was a lovely photo of Bridget Kelly [née O’Grady] in the chook run

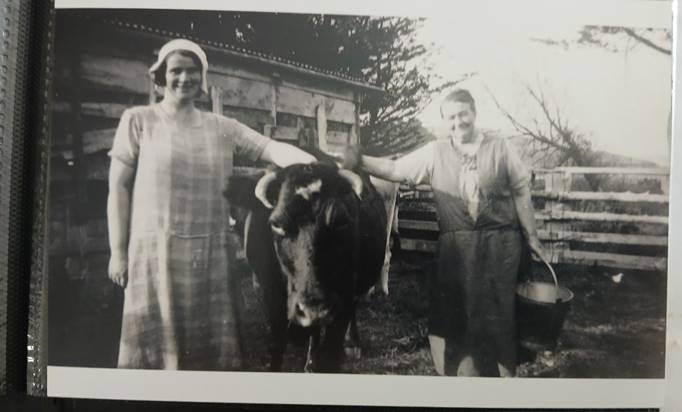

EJK- Where she’s crouched down with the chooks. So speaking of animals, I imagine there were a lot of animals you interacted with, and I’ve seen some beautiful photos with various dogs.

JEK- It was a dairy farm, I can’t remember how many they had there, but each cow had its own name. Nice names. So Colin knew them all. So presumably knew their milking patterns, those cows were milked twice a day

EJK- What happened to the cream?

JEK- The cream was separated, mechanically separated, and the skim milk was piped down to the pig pen for the pigs.

EJK- What happened to the rest of the milk, did that go off in a truck?

JEK- That would go, I presume it was picked up every morning, I can’t remember that, or every night, perhaps twice a day, I don’t know.

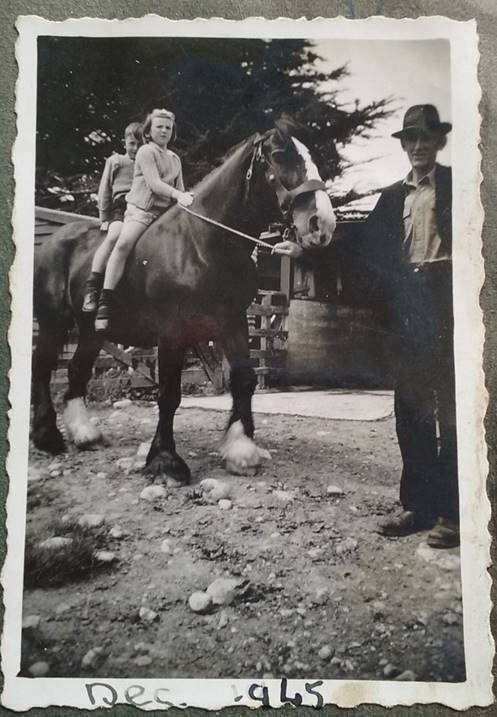

EJK- Yeah. There’s pictures of horse and cart and pictures of cars from the time you were on the farm, but I guess it was all mechanised by then, did they still have horses around when you were a child?

JEK- Yes, Uncle Colin had a draught horse which we rode occasionally, and we occasionally got scraped off under the macrocarpa trees when the horse didn’t want us on its back.

EJK- Did you ever get hurt falling off a horse?

JEK- No, we must have bounced. Once that horse was up the road near Colin’s mother’s place which was probably a mile and something up the road, and we were on it, can’t remember why, with Colin, and the horse refused to go over a little bridge, over a stream, just refused to go. Presumably it thought it was unsafe

EJK- So it didn’t stop so fast you went over the front?

JEK- It was a draught horse, they’re not quick, just ambled along and stopped

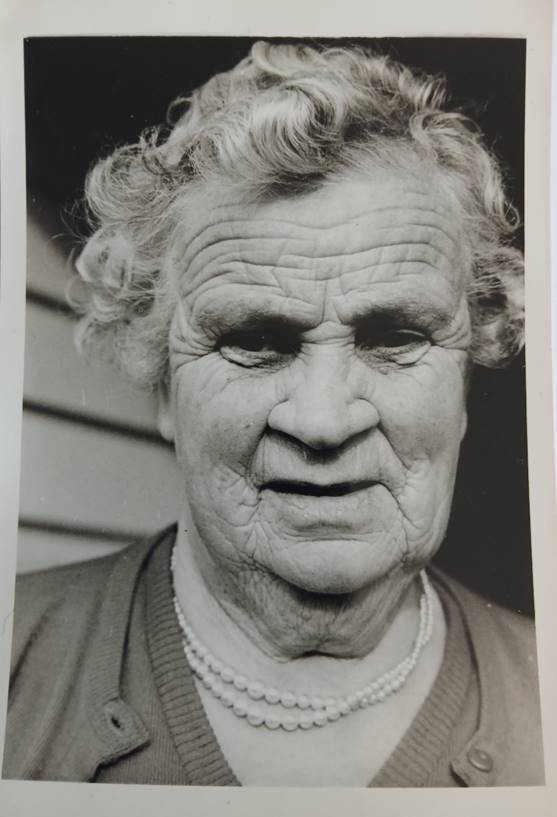

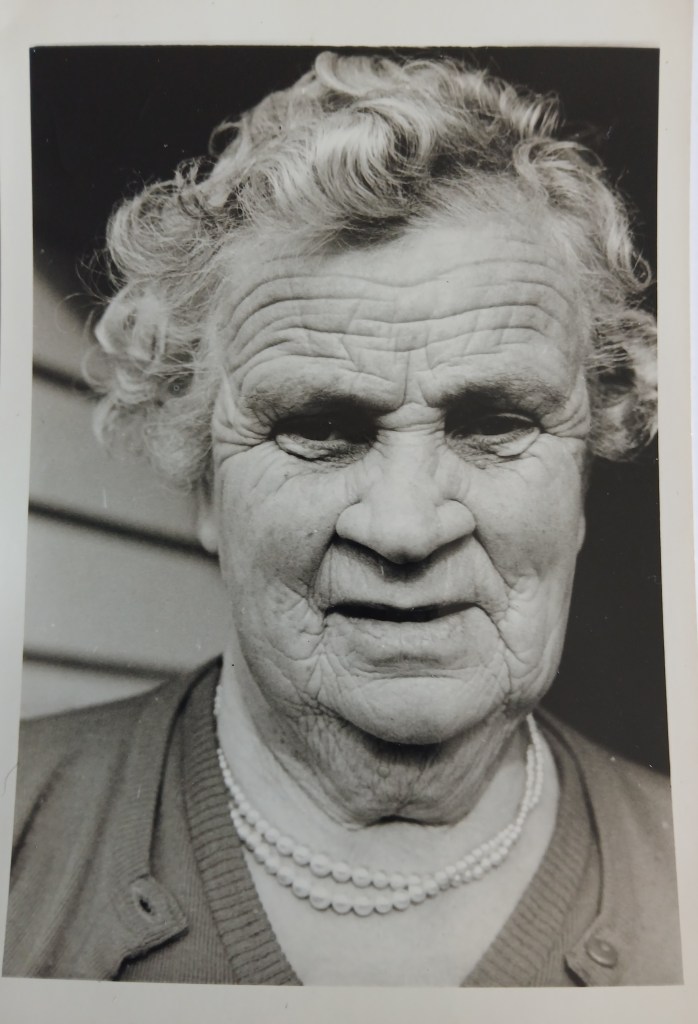

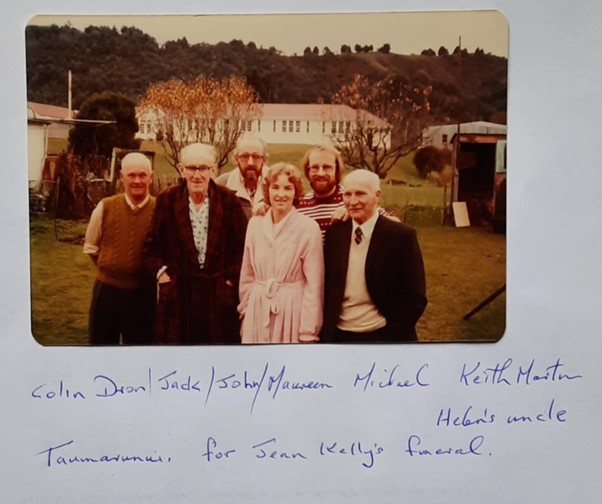

EJK- So Colin’s Mum was Annie Dron and she lived along the road as you say. Did you see much of Annie, was she an older lady when you knew her?

JEK- Oh yes. An old wrinkled face, but very pleasant. We did go up there occasionally I don’t know whether we saw inside Annie’s house. But the original farmhouse [on Middle Road, where Lizzie and Colin lived] was quite small, and interesting for kids because to get to our bedroom we had to go out the front door. Then turn to the right, along to a bedroom. In that bedroom was an old-fashioned dresser with several little drawers that pulled out, and they were full of Lizzie’s…what is the word I’m looking for?

EJK- Accessories?

JEK- Accessories yes, I’m sure they weren’t called that then, but brooches and strings of beads we’d find quite fascinating. And that room, that house also had a very sloping roof in the kitchen, so it sloped towards the bench; I wouldn’t be able to stand up at the bench now. And there’s a great story of Aunty Lizzie getting frightened by a mouse, and she hoisted herself up by her hands and, not stood, balanced, on her arms on the bench while a mouse [laughs] was running round, and I can’t tell you the end of the story because I don’t know what happened.

EJK- Wow [laughs]

JEK- I remember my mother being there once and there was a step from the living room into the passage, and Mum had been knitting, probably Fair Isle something because she had enormous numbers of balls of wool, and as she was going to bed, she put her foot up the step and dropped a ball of wool, and it took her several minutes to get up the steps because every time she picked up one ball of wool another one would fall down. And I can’t remember if there was any drink involved, but I suspect not as I can’t remember anyone drinking then, so Mum was just giggling her head off while dropping these balls of wool and picking them up

EJK- Were you helping her?

JEK- No, I was too little

EJK- And giggling

JEK- I’m sure I was

EJK- So if you had to go out the front door to get to the bedroom, was there a balcony all the way around?

JEK- There was a porch to the door. So, if you came out the front door and turned right there would have been a porch and a door facing. And I don’t know what happened to that house, did they actually demolish it? I don’t know, they may have done so, because Mrs Dron’s house in Short Road, a mile and half away, whatever, was moved, towed across the fields and placed upon the site of the original house, and that’s still the current house

EJK- Yes,it’s interesting. I think the house was demolished, because I’ve read the records about when the house got moved across, and Colin Dron had to contact the Crown to get permission to move the house because it was still Crown land and leasehold, and you wouldn’t have known, had any sense that it wasn’t their farm, I mean it was their farm but on a 999-year-lease.

JEK- No I didn’t know. I do remember Colin telling us that instead of going on the road obviously, you couldn’t take the house on the road, along the road and do a ninety degree turn, then along Main Road, so from Mrs Dron’s place it was taken diagonally across the fields. And Colin’s story was that he was busy cutting fences and moving posts and he kept looking behind him and he said the house was catching up! [laughter]

EJK-So that was the 1960s and that was Mrs Dron’s house, so Mrs Dron had died?

JEK- Presumably. In fact, I’ve just seen her gravestone [gestures to pictures] so you can look in there

EJK- OK. I was talking to Aunty Carole, your little sister, and she said one of her fondest memories of Mrs Dron was eating her Chocolate Marshmallow Shortbread Slice.

JEK- Oooh!

EJK- She said it was absolutely delicious and homemade and she can still remember the taste

JEK- Wow, that’s nice

EJK- My friend Ed and I made it and it’s delicious, and I sent photos to Aunty Carole in South Africa

JEK- Lovely!

EJK- Do you remember any particular food on the farm?

JEK- No, but going back to Mrs Dron’s house. My older sister Maureen was climbing over one of the fences which had a lot of barbed wire in it and she fell and gashed her leg quite badly. I can’t remember who wrapped it up, I don’t think we had to get hospital care, so Mrs Dron or Aunty Lizzie must have patched her up

EJK- Gosh. And so you and Maureen were closer in age

JEK- Yep

EJK- And then there’s a gap until the next kids. How long is it?

JEK- Probably four or five

EJK- And then you have Mike and Carole. Do you remember playing with them on the farm or were they so much younger you didn’t play together?

JEK- I can’t remember them there actually. Though there are photographs of Michael on the horse, but no, I can’t remember that. So presumably I played with Maureen more than the others.

EJK- Yes,that’s the impression I have. There’s a photo of you as a late teenager in very nicely tailored long trousers and Carole is on the horse behind you. She definitely looks a lot younger than you in the photo. But she talks about looking up to you and Maureen.

JEK- Yes, she’s eight years younger than me and born on my birthday.

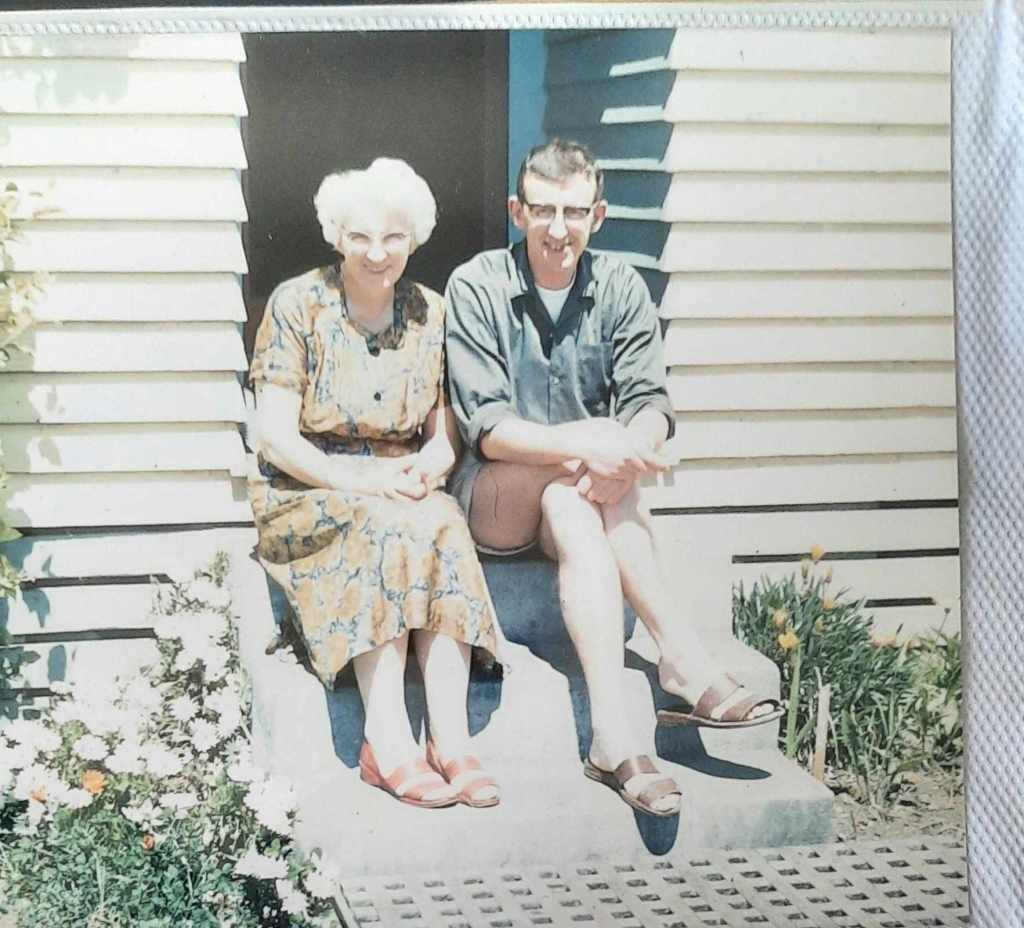

Below is a photo of John and Emma-Jean, Christmas 2025 on a ferry from Birkenhead to Auckland City.

Recording Two

EJK- So we’ve talked about some of the animals. Where did the dogs live?

JEK- Dog. I think it was dog singular, and the dog lived in the kennel outside, never an inside dog, because they were working dogs.

EJK- So did they corral cows?

JEK- Yeah,sorry what did you say, corral?

EJK- Corral, is that not the word?

JEK- That’ll do, yep.

EJK- I heard rumours that there were possums on the farm.

JEK- Oh,yes. At the front of the house there were huge macrocarpa trees. And I climbed up there once, there was a sort of a, you could find hollows in there. And I climbed up on this particular occasion and turned around and there was a possum, about two feet away from me, staring at me. I cannot remember what happened. Whether he screamed or I screamed, whether he ran away or I did. Or if I jumped out of the tree, I do not know

EJK-[laughs] so there were macrocarpa trees right in front of the house?

JEK- No, on the front of the property

EJK- So did that mean it was dark in the house?

JEK- Not that I recall

EJK- Because it’s all open now, it’s hard to imagine

JEK- It was in front of the garage. The garage door, to drive into the garage would have been level with the macrocarpas presumably

EJK- Right, and they would have been a wind break on a piece of big flat land

JEK- Yes

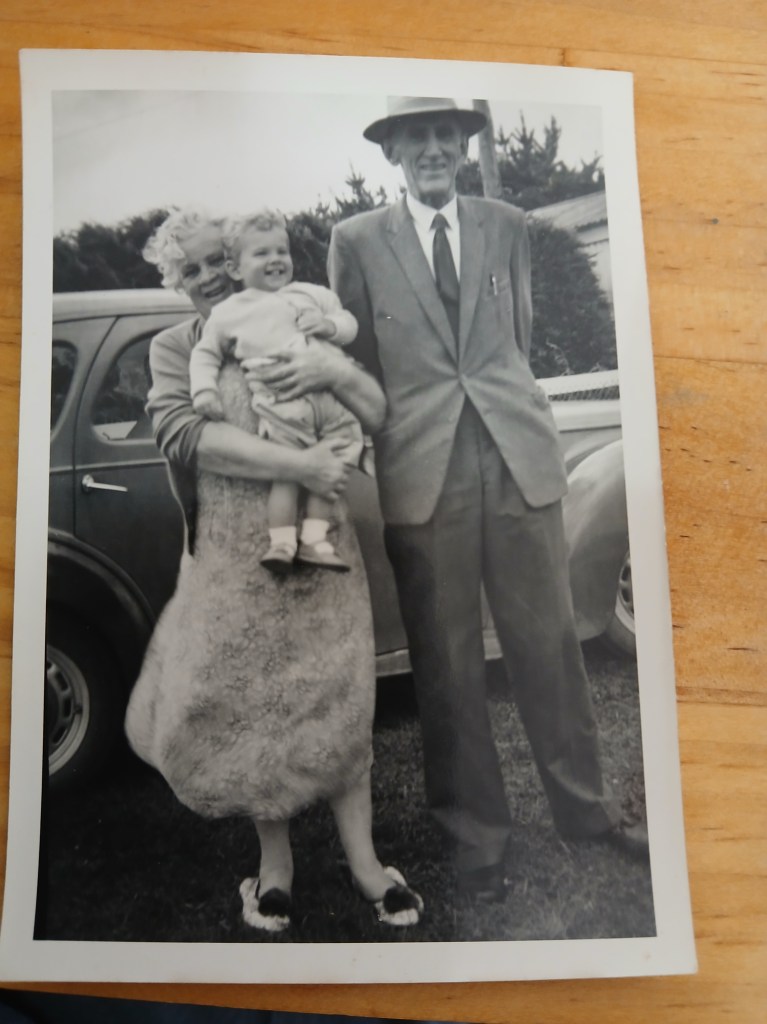

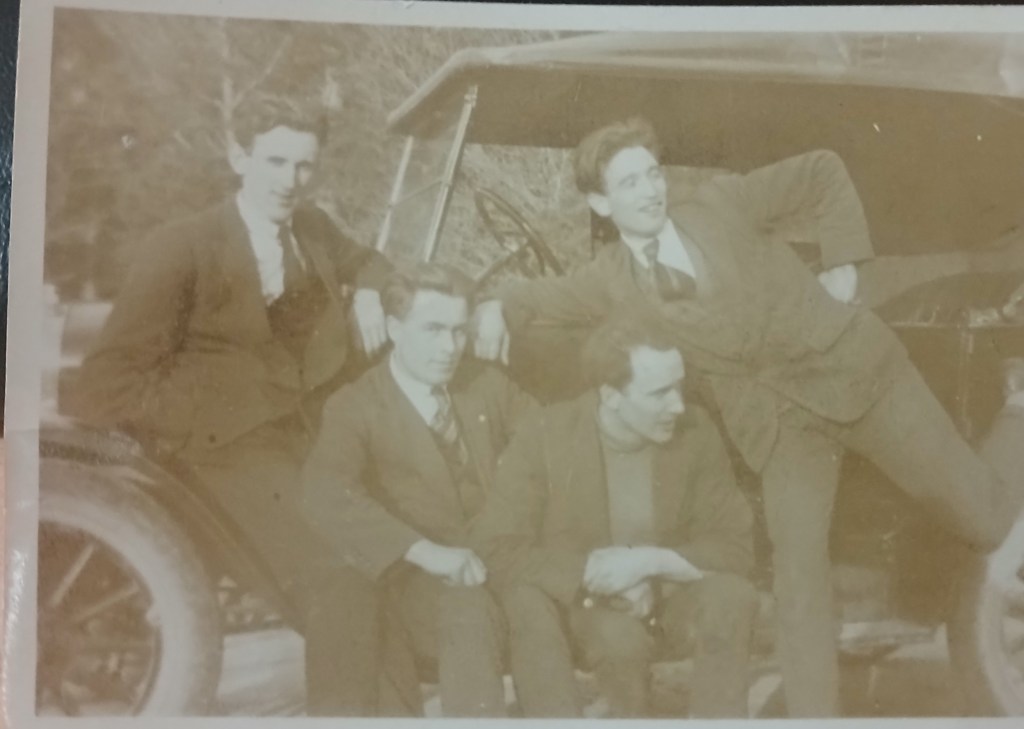

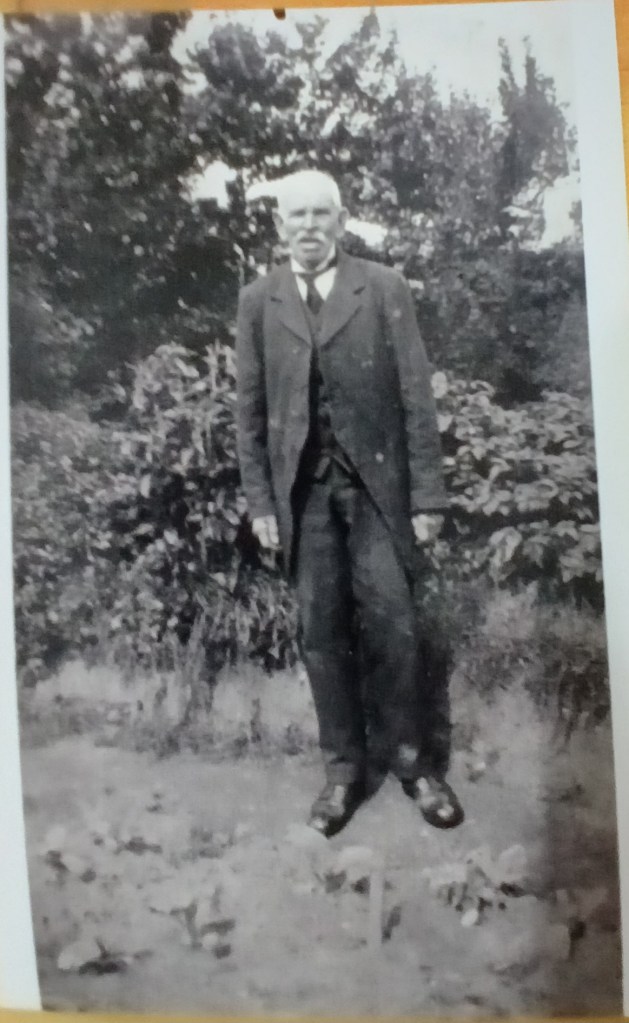

EJK- And there were buildings that changed on the property I suppose, but over the years there are photos with Grandad Jack in front of one particular building which seems to be an old shed?

JEK- yes, but that was in Short Rd. That was the original Dron house when Annie Dron’s parents lived there. It’s bigger than it looks in the photos, that was their home.

EJK- And so that’s on the Short Road property?

JEK- That’s where Mrs Dron used to live or nearby, it’s on the corner of that road, Dad visited it once or twice because there’s photographs of him there

EJK- And there’s photos usually with Dron family

JEK- Always with Dron family

EJK- So Grandad, did he get to have holidays with you there or did he just come for visits while he was working?

JEK- Yeah, he used to, I think he used to come. I don’t know, maybe he did send us for holidays while he was working.

EJK-He must have had holidays sometimes, you mentioned the baches, so sometimes you’d go altogether

JEK-Yeah, but we’re talking about Pahīatua, I can’t remember Dad being there but he must have been, but not for holidays perhaps, I don’t know

EJK- Did you notice frogs or insects?

JEK- There was a paddock across the road which had frogs in it yes, we could hear them at night.

EJK- So were there swampy bits?

JEK- Well, enough for frogs

EJK- Who owned the property across the [Middle Road] road when you were a kid, do you know?

JEK- No, I don’t know. I don’t know whether it was part of Jim’s corner or not

EJK- Yeah, because we’ve been told later that was Jim’s Section but you didn’t know that at the time

JEK- I don’t know if that was the other side of the main road though

EJK- The other side of Middle Road?

JEK- That’s where the swamp was

EJK- OK. To town, to town with Aunty Lizzie. So did you go to town when you were on the farm?

JEK- Yes. I don’t know how often we went to town, not very often. But Lizzie would be dressed up, as women did in those days, there was a picture theatre there, and I seem to recall it was the old style, you know, with all the curtains going up and sideways, and lots of coloured lights before the film. But mainly Lizzie went there to do her shopping I suspect. But I don’t remember her buying groceries, that was long before supermarkets of course.

EJK- Mm, the farm can’t have been completely self-sufficient.

JEK- As I say, I can’t remember her buying groceries. We would have had milk from the farm, meat from the farm, and there must have been a vegetable garden somewhere or other, but I can’t remember where it was.

EJK- Yeah, because we’ve got letters from your Mum describing the food she brought home from the farm.

JEK- Yes, I just can’t remember where the garden was

EJK- And fruit. Do you remember fruit trees?

JEK- No

EJK- You weren’t so aware of gardens then or there wasn’t much of a garden. What about other neighbours, do you remember neighbours apart from the Drons?

JEK- The next people up the road were Mr Anderson who married Mrs Anderson [laughs], she was a town woman and all I can remember about her was she never went out on the farm and she wasn’t happy living on a farm, and that’s all I can remember about them, I was pretty young. And the next place up the road was the Pilkingtons. They were a fairly well-known family in the area. Mervin was the son, the same age roughly as my older sister, so he used to come down and play with us occasionally, and I gather he died when he was about forty. I don’t know what of.

EJK- Any other neighbours you remember?

JEK- No. And they weren’t close neighbours. The Andersons would have been half a mile down the road perhaps, and another half a mile to the Pilkingtons. My Uncle was friendly with the people behind on the main road

EJK- Were they the Letts?

JEK- The Letts, yes

EJK- And there’s a note you wrote about exploring the bush behind the Letts?

JEK- Yeah, it wasn’t Colin’s property I know, we used to go up a hill and there was a tree there, in the bush. I don’t know if we put our initials on it or not, on the tree, but we always felt we were doing something illegal up there so it had that thrill of illegality

EJK- [laughs] Were there creeks or rivers or streams you used to play in?

JEK- Yes, the creek ran through Colin’s property, it must have gone under the road, I can certainly remember it, but I don’t know how it got under the road, it must have gone under somehow or other. But occasionally Colin would bait pins I think and we’d try to catch eels in the creek. I was forbidden to go on my own and of course did on one occasion and slid down the bank and ended up inches away from the water unable to move, and eventually extricated myself without getting wet.

EJK- So you didn’t yell for help?

JEK- Good heavens no

EJK- Would you have been in trouble if you yelled for help?

JEK- Quite possibly yes, or my sister would have laughed and pushed me in, I don’t know

EJK- Was Maureen prone to teasing?

JEK- Yes

EJK- In a nice way or a mean way?

JEK- Both

EJK- OK [laughs] that sounds like my sisters. The other neighbour story you told me that I found quite sad was about a neighbour further away that you remember vaguely visiting as a child, and the child [there] was not well and didn’t really leave the house much.

JEK- Yes,they weren’t neighbours at all. They were the Diamond family who lived in Pahīatua, and they must have been friends with Lizzie because we went round there once or twice. And the boy who was possibly my age or younger at the time was…unaware. So I don’t know whether he was deaf, dumb and blind, yes he was blind, and they’d just kept him at home, they hadn’t tried to get him educated or any special care so his behaviour when we were there was bizarre, because he didn’t know any different. I’m not going to describe it.

EJK- What did you think as a child?

JEK- Don’t know. I was younger than a teenager possibly.

EJK- And did anyone talk to you about it?

JEK- Nope

EJK- Gosh, it’s funny isn’t it? Because we tend to talk about everything, you probably think I talk about more than I should, but in that circumstance as a child I would have asked heaps of questions.

JEK- Well I got the impression because maybe I asked that he hadn’t been educated in any way. So perhaps I asked. Perhaps I was told, I don’t know.

EJK- Did you know, growing up, anyone in Pahīatua who was different or mentally unwell or did you hear stories of people who were different?

JEK- No, not at all

EJK- So overall, what was it like being in Pahīatua for you as a kid?

JEK- Oh, it was lovely. It was always summer, we were able to, probably when we were older, we were able to go down to the Mangatainoka River to swim, that was, I don’t know whether we walked or took a bike, it was a mile or two, past the main road. Other activities, I can’t really remember really.

EJK- Do you remember eating?

JEK- No

EJK- You mentioned in your notes a smoked ham?

JEK- Yes, Colin being a farmer, he’d obviously killed a pig and smoked it, and it was hanging from the ceiling in the living room. We never got to eat it.

EJK- So was it curing? How long did it take to cure?

JEK- Yes,I don’t know.

EJK- I would have been slobbering over it. Did you go out and have a look at the milking, or help with the milking?

JEK- We did when we were younger, but as we got older we didn’t for some reason. I don’t think we actually helped with it, we would probably get in the way. But I do remember the cat having milk squirted into his mouth, or her mouth.

EJK- You’ve written a note about haymaking too

JEK- Well that was a big thing every year. And all the people in the area helped everybody. I think there was probably one haymaking machine, and that was, I don’t know, loaned around. I remember Colin being concerned one particular year because all the hay was out in the field drying and if hay gets wet and it’s stored it spontaneously combusts because the heat builds up inside it. So you can’t store it once it’s wet and possibly you’d lose a lot of hay before it was put away.

EJK- Gosh, yeah, so much depended on the weather. And was the toilet outside or inside?

JEK- The toilet was outside, you had to walk outside to it. All the photos of kids are always outside a shed at the back of the farm, that’s the toilet. It can’t have been attached to the sewage system now that I think about it. The seat was more than a yard wide with a hole in it, and it had been there so long it was full of borer holes which was quite fascinating while you were sitting on it

EJK- So was it a long drop?

JEK- It must have been. It certainly wasn’t on town sewage. But I can’t remember it having to be emptied, so I really don’t know.

EJK- And you don’t remember a smell? You stood beside it for photos.

JEK- No. You didn’t stand beside, next door to it, I don’t remember a smell.

EJK- I was also wondering about accents. If you remembered different people having different accents, or if they all sounded the same to you?

JEK- Well Lizzie had a very strong lrish accent.

EJK- Stronger than Grandad Jack?

JEK- Oh yes. Well, she didn’t have as much contact as he would have had in cities.

EJK- So her accent stayed the same. Did Annie Dron have an accent?

JEK- Not that I recall

EJK- She was NZ-born but had Scots and Norwegian parents [she was a Larson before she married]. And you knew there was some kind of Scandinavian link but you didn’t know what it was. How did you know that if she had no accent?

JEK- I have no idea

EJK- And then when you and I looked up her Ancestry records we found her parents were Norwegian immigrants who came to take down the Seventy Mile and Forty Mile Bush

JEK- Yes

EJK- What might Aunty Lizzie’s attitudes to politeness have been? Were there types of behaviour which she thought should be different around men and women for example?

JEK- I do remember when she was, she must have been making beds in our bedroom and Mervin Pilkington was in the room as well, and she didn’t, she didn’t want him there but she certainly wasn’t going to say so. So when her back was to him she was mouthing at me that he shouldn’t be there. And being a little bastard at the time I said ‘what are you saying Aunty Lizzie?’

EJK- So did she think it was improper?

JEK- Yes, indeed. It was the same as having to wear a hat when you went to town and possibly gloves, though I don’t remember that.

EJK- Do you remember anyone who wasn’t white in Pahīatua?

JEK- No

EJK- Were you kids ever allowed on the train on your own?

JEK- We went on our own from Wellington, I can’t remember going from Frankton [Junction, another railway settlement the family lived in out of Hamilton]

EJK- What’s it like when we’ve been back to Pahīatua recently for you?

JEK- Well it’s interesting because some things are the same and some are not. Where the Dron house was there is nothing recognizable; a few years ago there were fences and a chimney I recognized, but not anymore. And I don’t even know what that land is used for, if it’s still a small plot or an acreage or not.

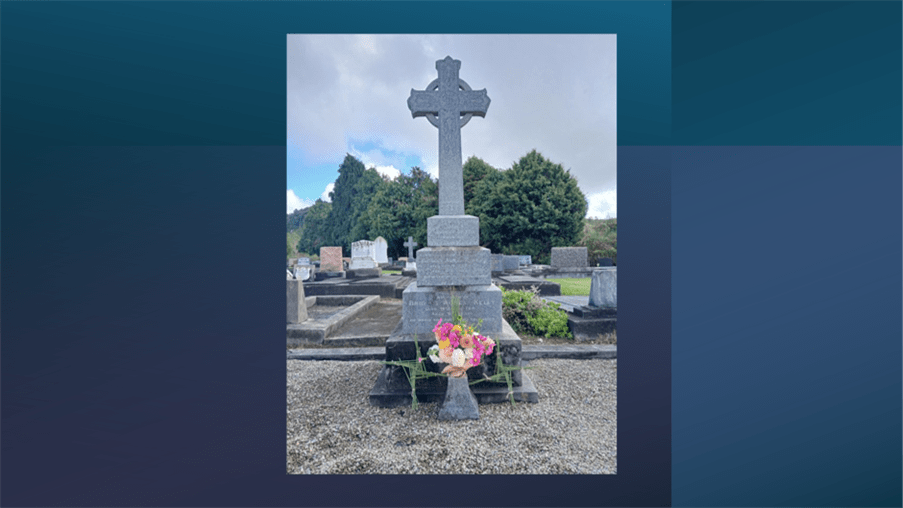

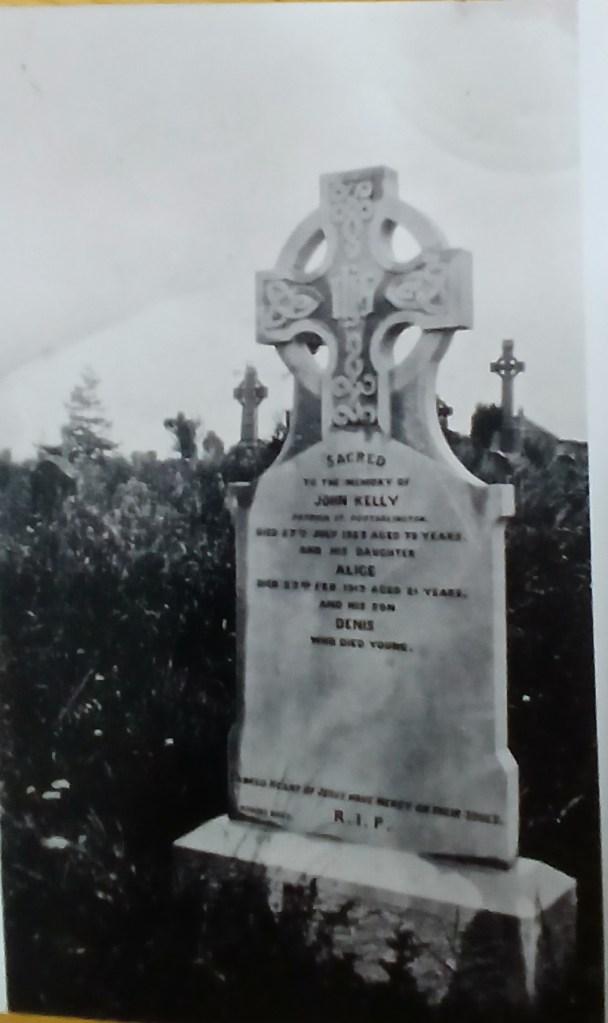

EJK- And the other thing we always do is go to the Mangatainoka Cemetery. Can you just describe that, the grave and who’s there?

JEK- Well there is a big family grave, it’s not a Kelly one really, Dad’s Uncle is there, the family…

EJK- William Kelly married into

JEK- So there’s a big big tall grave which presupposes if that’s the word that they had money as it’s a big memorial

EJK- Christian Irish Catholic look. So there’s Brigit O’Grady the Widow, the mother who came over with her children Bridget and James, there’s William Kelly, our relative in there as well, that’s everybody as well isn’t it? But the Drons are not in the same grave, they’ve got a more modern grave further along.

JEK- Yes,and I think Annie Dron’s grave is in there [at Mangatainoka] as well but I’ve never found it.

EJK- Was there anything else you wanted to talk about?

JEK- No, that’s it.

EJK-Thank you, there was lots in there I hadn’t heard before.

![20151119_161914[1]](https://kellyogradydronfamilyhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/20151119_1619141.jpg)