By Dr Emma-Jean Kelly

John and Maureen Kelly on the horse, with their Dad Jack Kelly holding the reins at Pahiatua, December 1945

Great the Grief, Great the Memories

Introduction:

The history of Pākehā purchase of Māori land in the Forty Mile and Seventy Mile Bush area is described in detail in an excellent thesis ‘Pahiatua Borough: The Formative Years 1881 – 1892’ by Byron John Bentley, 1973, Massey University, and in the Waitaingi Tribunal Reports for the area, both available online.

Across the British Empire, Waste Lands Acts were one of the legal instruments used to alienate land from Indigenous populations by the Crown, who would then hold the land as endowments, and ultimately lease or sell that land to white settlers during the various stages of the expansion of colonisation, including for the development of white villages, towns and their amenities. Acts of outright confiscation have (deservedly) gained much attention, but legislation such as the Waste Lands Acts were used for many decades (indeed, into the twentieth century) to systematically alienate Indigenous peoples from their lands and in turn ensure white settlers had the land they wanted.[1] There was an attitude from white settlers that Māori ‘…did not utilise their lands in accordance with European standards…'[which made them]‘…a barrier to progress.’[2]

The use of Public Works Acts and purchases (by private individuals and the state) targeting individuals rather than the wider hapū and iwi were also undertaken to alienate land from the wider group, supported by the Native Land Court and its processes.

Bentley says the ’70 Mile Bush’ was part of a number of public works schemes, and in the 1870s Scandinavians were brought out to New Zealand under the auspices of these schemes. ‘These immigrants were settled at Norsewood and Mauriceville, the northern and southern extremities of the “70 Mile Bush”, for the purpose of bush felling and roadmaking’ (p.3). The ’40 Mile Bush’ area nearer to Pahiatua wasn’t impacted so much by them but they successfully decreased the dimensions of the daunting bushland, and constructed the road through the bush linking Hawkes Bay with the Warirarapa. In the north, Woodville was founded in 1874 (p.3, Bentley). This is significant to our story as Brigid O’Grady lived there with her children Bridget and James before moving to Pahiatua. Additionally, Colin Dron who lived with his parents on Section 23 of the Mangahao Block XVIII Pahiatua Special Village Settlement, who would marry our Aunty Lizzie Kelly in Pahiatua in 1941 was descended from these northern European pioneers. Colin’s paternal grandfather Anders Larsen Danstorp was born in Rakkestad, Ostfold, Norway (1841-1898) and his Mother Anna Thorina Anderstatter (1842-1922). They were some of those Norwegian immigrants, sailing on the Hovding in 1872 to New Zealand with the family including Colin’s Mum Annie Sophia Dron (née Larsen) who died 6 November 1958.[3] Colin’s Dad Angus Dron was born in 1867 and died on 19 August 1933.

In the 1880s, Masterton nurseryman William Wilson McCardle was a member of both the Wairarapa North County Council and the Wellington Waste Lands Board (pp 4, 5, Bentley). While Samuel Locke, a government surveyor and agent ‘purchased’ large sections of the 40 Mile Bush in 1870 and 1871 from local Māori (Bentley, p.2) it was McCardle who began to explore what would become Pahiatua County in 1876. McCardle represented the Alfredton Riding and had the present County of Pahiatua formed in a separate riding of the Wairarapa North County Council (Bentley, p.4).

According to Bentley, ‘Because Pahiatua land had been purchased from the Maoris it was designated “waste land”, therefore its sale came under the control of the government and membership of this body gave him more leverage in his desire to settle the Pahiatua land.’ (p.5).

Under legislation influenced by McCardle, the Land Act of 1877 and its amendment in 1879 led to Pahiatua being the first block settled under central government legislation. It allowed for the area to be a testing ground for various types of settlement and land purchase including Special Village Settlements, which our family were able to settle under (p.5).

There was in fact an ‘incomprehensible array of legislation’ in connection with Māori land’ according to Dr Peter Meihana.[4] Papatupu land is traditionally owned Indigenous land under customary title, without a European title. Efforts by settler governments over time sought to alienate (remove) this land from Māori owners by converting title to European-style ownership (Meihana p.196).

Just a handful of the legislation which streamlined this process included the aforementioned Wastelands Acts as well as the 1891 Land and Income Assessment Act, the Native Lands Purchase Act 1892, and the Native Land (Validation of Titles) Act 1892 (and 1893). The Native Land Court Act 1894 section 117 restored full pre-emption (first right to buy for Government).

The Land Act 1892 made provision for a variety of land alienation options including 25-year lease with right of purchase, and 999-year lease. Joseph Ward’s 1894 Advances to Settlers Act then established an Office ‘empowered to provide both leaseholders and freeholders with cheap loans to develop their lands.’[5]

Some of these provisions allowed for our family to purchase sections in the Pahiatua Special Village Settlement in the 1880s and 1890s, with cheap loans and government advances. They were considered ‘good settlers’, with Brigid O’Grady described as a ‘desirable settler’, despite the generally held prejudice against Irish Catholics at the time. Māori could not use the same provisions to buy sections, as they held their land communally. It was unthinkable for most Māori to own land, let alone hold an individual title to it, though of course some individuals did claim ownership of an area so they could sell it for individual profit.

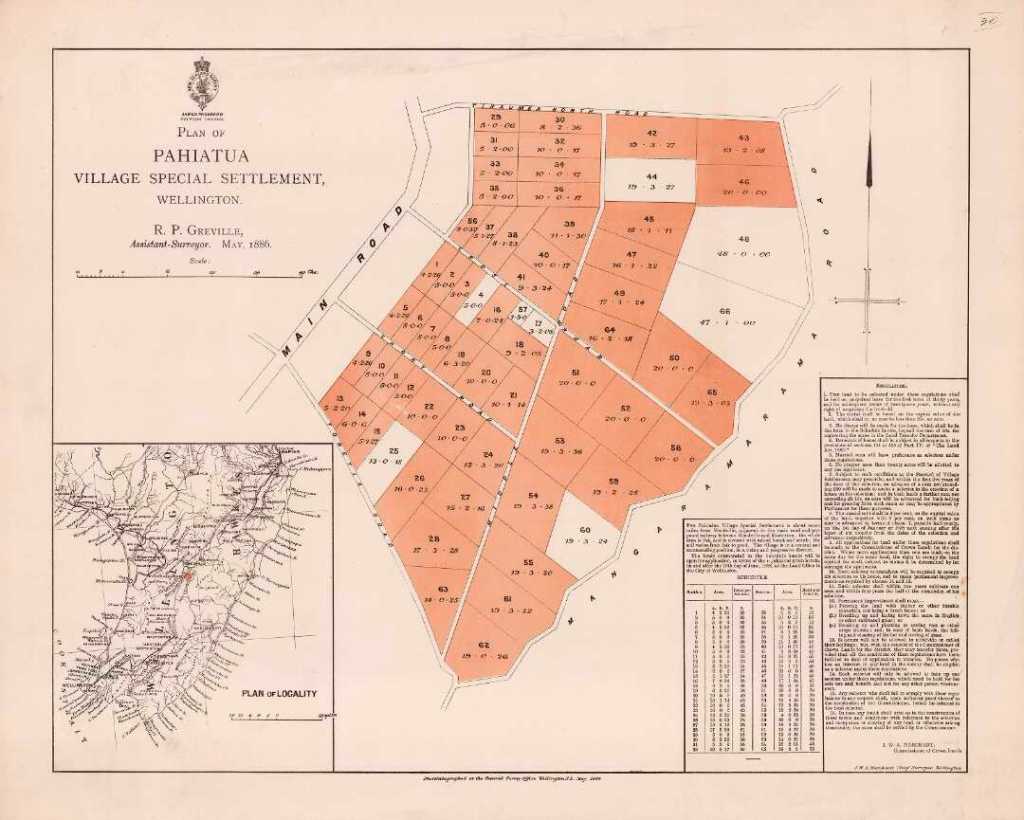

Pahiatua Special Village Settlement, the O’Grady, Dron and Kelly clan eventually owned the bottom of the wedge, Sections 62 and 63. Photo Archives NZ.

The O’Gradys come to New Zealand

Of course the Irish have their own long history of colonisation, and so it’s always surprising to me that they seemed happy to take the land of other Indigenous peoples. But they may have harboured prejudice against Māori who they were encouraged to perceive as ‘savages’, despite Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which guarantee Māori their lands and other taonga. A local history by Henry. J. Angelini called ‘Mangatainoka Memories’ actually has a passage describing the Dron/Larsen family women in the early days of the Norwegians’ arrival being ‘…terrified by some Maoris who were merely offering them food but they misunderstood the intention’ (p.136, 1989 edition Pahiatua Printing Company).

Brigid O’Grady (née Tracey) was from Tipperary in Ireland and was married to James, a shoemaker, who died (we’re not sure how, this is one of the things it would be interesting to learn). Brigid and James had two children who carried their names, and so we will call the daughter Bridget. She was the eldest, and James will be called Jim, he was the youngest.

The O’Gradys may have moved to Limerick because James Snr had died. When Brigid brought the children to New Zealand, she was named as a housekeeper from Limerick on the emigration paperwork.

In 1884 the little family took an assisted emigration ship called Victory to Napier, North Island, New Zealand.

The wooden chest which carried Brigid, Bridget and James’ belongings to New Zealand in 1884 on the Victory.

Brigid was 34, Bridget was 13, Jim was 10. The British Government paid £39 for their passage as they were considered ‘two and a half people’.

Meanwhile in Pahiatua, J.W.Beaufort was the first selector mentioned in the Section 62, VHLP491 Mangahao Block XVIII Pahiatua Special Village Settlement file from Archives NZ (ANZ). He held the section from 1886.[6]

By 1888 the O’Gradys were based in Woodville, and Brigid’s occupation was listed as ‘Farmer’. Brigid applied for a transfer of the Section 62 lease from Beaufort who had been trying for some time to find a ‘good settler’ who would take it off his hands. According to the Commissioner for Crown Lands the section was 19 acres and 24 perches.[7] According to the law, these selectors under this particular scheme were only allowed a maximum of 20 acres.

In all legal documents, Brigid signs her name with a cross (±); as the lawyer notes, she cannot write.

There was discussion about this application between the Crown Lands Ranger for Pahiatua and the Commissioner of Crown Lands Office as ‘married men will have preference as selectors’, according to the maps of the area. However, her status as a widow apparently makes her eligible, and furthermore she receives a letter of support –

‘I have made every enquiry in connection with Mrs O’Grady’s character and position and find that she is a desirable settler’, (1890, Steward Pahiatua, A.R. Mackay, Esquire).

Brigid O’Grady was granted the lease for the section and signed the paperwork on 28th December 1888.

Brigid was now 38 years old, Bridget is 17, and Jim 14 when they moved to Pahiatua. The section is at the corner of Middle Rd and a road the family call at the time Toretea Rd, but it has various names over the years on the maps. It is at the bottom wedge of the Pahiatua Special Village Settlements maps.

Three years later in 1891, Bridget O’Grady was 20 and married William Kelly, the author’s Great Great Great Uncle. According to the marriage certificate he is a Labourer, from County Laoise, and is 32 years old. The ceremony was at St Brigid’s Church in Pahiatua, and Jim, now 17 was witness, along with Mary Cooper.

In 1892, the report of the Crown Lands Ranger for the fourth year of their residence says they had cultivated 10 of the 19 acres and have built fences, buildings and a garden.

In 1894, Brigid O’Grady made a request to the Commissioner of Crown Lands for her tenure to be converted to a Lease in Perpetuity. She was told it was not possible under the Land Act in a special settlement (Land and Survey Office letter).

However in 1895, George Dunn the leaseholder over the other side of Middle Road on Section 63 also applied for a Lease in Perpetuity. This was granted, and he received a Government Advances to Settlers Act 1894 loan.[8]

So Brigid Kelly applied again in 1895. She said, ‘I see the last meeting of Land Board that several applicants were granted their leases…’ and so she was reapplying for hers. It may be that she had been talking to her neighbour George over the road.

This letter is written from ‘Toretea Rd’, Pahiatua, and has a number of spelling mistakes (on some maps the road is called ‘Toritea’. Given Brigid continued to sign her name with a mark for the rest of her life in letters written by her solicitor, I wonder if Jim, Bridget or William wrote this letter.

The Commissioner of Crown Lands then agreed to her conversion from tenure to Lease in Perpetuity, but she received a letter saying she owed money. She replied that she disagreed with this demand, saying that she had been overcharged.

‘I received a demand…for eight shillings and five pence more than my ordinary rent and I want to know what it is for as I have Paid Up all rents and lease expenses demanded of me’ (dated April 26 1895 from Toretea Rd).

In 1897 it appeared there was a survey of the land, and the Land and Survey Office notified Brigid that the land is actually 19 acres, 1 rood and 8 perches, not 19 acres 26 perches. This led to a recalculation of monies owed, and the annual rental became £2: 16s: 5d, and the half yearly payment (which appears to be a separate cost) became £1:18s:3d. It is paid promptly.

In 1899 George Dunn over the road applied to transfer his section to Brigid’s son Jim O’Grady. According to the paperwork, James O’Grady already held Section 1, Block IV, Mt Cerberus, Hawkes Bay. It was 100 acres but he hadn’t been meeting the residential condition by living there, so he was transferring it to another settler. Under the terms and conditions of these leases, the settler could not lease another section if they were not living there and cultivating it. James, like George before him, received a cheap government loan to help with the purchase of the lease.

But by 1903, Jim was very ill. According to his brother-in-law William, Jim had threatened to kill his mother and sister. Jim told the doctor that he was seeing visions of hell, which was like digging potatoes. The pope visited him in his visions and there were also circus animals. Jim was committed to the Auckland Asylum and eventually moved to Porirua Asylum until his death in 1942. So far as we know, his family never visited him. When his sister Bridget died, a long obituary is written in the local paper for her, but it did not mention that she had a brother.

In 1916, Jim had been continually in mental hospitals for 13 years, and his mother, called ‘Bridget O’Grady’ on the paperwork, applied to take over Section 63 along with Section 62. She explained she had been looking after it since Jim was incarcerated. She did not mention her daughter Bridget or son-in-law William. There must have been a relaxation of the 20 acre-only rule, as she was granted both sections. However, when we talked to the family who now own the land a few years ago, they asked us why the triangular corner of Section 63, adjacent to Middle Road and what was called Toratea/Toratia and is now called Pahiatua-Pongoroa Rd, was called ‘Jim’s Field’. So for whatever reason, a memory of Jim remained on the land.

In 1920, William Kelly died. On 26 February 1922, Brigid O’Grady died intestate. In 1923, at the end of the Irish Civil War, William’s niece from County Laoise, Elizabeth (Lizzie) Mary Kelly travelled to Pahiatua to help on the farm.

In 1936 there was a valuation of Section 62. The occupier was named as ‘O’Grady, Bridget. Dec’d’. The capital value was £831, the unimproved values are £118 and £246 and the value of improvements was deemed to be £467.

Bridget Kelly (née O’Grady) on the farm with the chooks (undated). From Kelly Family Bible, originally given to Bridget in 1891 upon her marriage to William Kelly. Collection of John Eamon Kelly, Auckland, New Zealand.

On the 14th August 1940, Bridget Agnes Kelly died. According to the Kelly family letters, Bridget’s will left the farm to an O’Grady nephew in Australia that no one in the Kelly/Dron clan knew.

In 1941, with the support of her brothers Michael Joseph Kelly[9], engine driver, and Jack Kelly (the author’s paternal grandfather), railroad engineer, Elizabeth Mary Dron bought both sections 62 and 63. She was by then married to Colin Dron, from Section 23 around the corner (the grandson of the Norwegian pioneer from Norsewood).[10] They paid £1200 for the sections. The documentation stated Lizzie had £750 from Brigid O’Grady’s estate, the lessee’s equity was £1192. She was 41 and had £200. Colin had stock and plant worth £250. She was applying £400 ‘to pay consideration’ and the balance of £800 to remain on the mortgage.

It was always discussed in the Kelly family that Lizzie and Colin married so she could keep the farm. We don’t know if this is true, but there are letters between Jack and Michael Joseph Kelly, Lizzie’s brothers, angry with Bridget Kelly for not leaving the farm to Lizzie who had worked it (presumably for free) since 1923. Bridget appeared never to have resolved the legalities of her own mother Brigid’s death in 1922, so this left her husband’s nephew Michael Joseph Kelly as trustee until the issues of ownership could be resolved. It appears to have been a stressful time for the families.

On 10th November 1942, James O’Grady died. The family sent a telegram via their lawyers to Porirua Asylum saying they should ‘spare no expense’ to send his body home. He’s buried in the large Irish Catholic Cross monument for the O’Gradys, Drons and Kellys at Mangatainoka Cemetery.

Kelly, Dron, O’Grady family grave, Mangatainoka Cemetery.

In 1962 Colin Dron applied to the Commissioner of Crown Lands to move his mother’s house from Section 23 (10 acres) to Section 62. John Kelly, Lizzie’s nephew, remembers Colin telling stories of running across the fields in front of the tractor pulling the house, cutting the fence wire for the house to be wheeled over the fields.

On the 4th of the September 1975 Lizzie Kelly died at 8am. Sections 62 and 63 were transferred to Colin. In 1983, Colin was offered the opportunity to make the sections freehold, and he does so for a fee of about $200.

The Vial family were neighbours and farmers in the area since World War One. Graeme Vial remembers listening to the adults talk around the table about the opportunity to freehold, though he didn’t understand it at the time. The families also played games in the evenings together.

Graeme was a teenager and allergic to milk when Colin began to need help with the cows on the farm after Lizzie had died. Graeme helped, despite his allergy. When Colin died in 1998[11], he left the farm to the Vials, who had been such good friends and neighbours to the family. This feels like a wonderful decision which ensured the close community remained intact.

Graeme held onto some things in the house, and has now returned them to the Kellys, who finally showed up for a visit in the 2010s. The 1884 wooden travelling chest of Brigid O’Grady, with the message ‘Wanted on Journey’ printed on the front is now a prized family possession. It has the name ‘James’ scrawled in a childish hand inside in pencil. This led to Emma-Jean asking some questions, and our cousin Gerard McGreevy telling us the story of ‘poor Jim’ and his life and death at the Porirua Asylum. She has written a separate story about this which is available via the National Library website ‘The Disappearance of James O’Grady, 2022, New Zealand Journal of Public History’.

John Kelly (born 1936), Maureen his big sister (deceased), Carole, the youngest, and Michael Kelly were Jack and Jean Kelly (née Martin)’s children. Jack worked on the railways so the family moved a number of times, he was a nephew of William Kelly, who married Bridget O’Grady. And so the Pahiatua Farm was a constant in their lives, and the kids went there for holidays, often driven in the old farm truck over the very steep Rimutaka Ranges by Uncle Colin.

John remembers Colin’s Mum always being referred to as Mrs Dron, and the farming community working together to do the hay baling on all the farms at once. Carole remembers Mrs Dron made a ‘great Choc marshmallow short bread’. Carole also remembers Mrs Dron at her dying time. Over the road from the farmhouse was apparently the frog pond, and they could hear the frogs.

Conclusion

We would love to see any pictures of William Kelly and James O’Grady (if they exist). William in particular hardly comes up in the records, beyond his marriage certificate in 1891. We don’t even know when he came to New Zealand as we’re not aware he had a middle name to distinguish him from all the other William Kellys from Ireland coming out during the 1800s.

Beyond photos, if anyone has any memories of the O’Grady, Dron and Kelly clan we’d love to hear from you.

Dr Emma-Jean Kelly, Berhampore, Wellington, mjeankelly@gmail.com

Annie Sophia Larsen Dron (‘Mrs Dron’) with Colin (her son) and Aunty Lizzie Dron (née Kelly) Date unknown, collection of John Eamon Kelly, Auckland, New Zealand.

References:

Archives NZ files

Section 62 Archives NZ R25032083, VHLP491 (Brigid O’Grady’s lease from 1888).

Section 63 Archives NZ R25032095, VHLP534 (James O’Grady’s lease from 1899).

Articles

Kelly, Emma-Jean. The Disappearance of James O’Grady.

New Zealand journal of public history, 2022; v.8:p.36-59; issn: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/51127528

Theses

Bentley, Byron John. Pahiatua Borough: The Formative Years 1881 – 1892’ 1973, Massey University (available online).

Books

Angelini, Henry.J. Mangatainoka Memories, 1989 edition, Pahitua Printing Co. Ltd.

John Eamon Kelly holds many family photos and papers at home in Auckland, New Zealand, and Pam Kelly in Sydney Australia did much of the archival research which we have been able to build upon. Thank you Pam and John! Carole Raffinetti has been very generous in sharing her memories from South Africa, and was also the one brave enough to knock on the farmhouse door to see if anyone remembered our family. Graeme Vial then stepped up and shared many things which have helped us to get this far.

Great the Grief, Great the Memories.

[1] For example, Reserves and other Lands Disposal and Public Bodies Empowering Act 1924 https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1924/0055/latest/whole.html?search=sw_096be8ed8009bc1a_wellington_25_se&p=1

[2] Peter N. Meihana, ‘The Paradox of Maori Privilege: Historical Constructions of Maori Privilege circa 1769 to 1940’, Thesis for Doctor of Philosophy, Massey University, Manawatu, New Zealand, 2015, p.8

[3] Colin’s paternal Grandmother was Agnes Drummond, born in 1806 in Methven, Perthshire, Scotland. She died in 1880 in Waimea West, Nelson. Colin’s Grandfather John Dron was born in Dunbarney, Perthshire, Scotland and died on 16 February 1885 in Waimea West, Nelson, New Zealand. He may have an Archives NZ file (I haven’t checked it yet) R20157544 Wellington Repository.

[4] Meihana, Peter N. The Paradox of Maori Privilege: Historical Constructions of Maori Privilege circa 1769 to 1940. PhD Thesis Massey University, 2015, pp.183, 184.

[5] Meihana, Peter N. The Paradox of Maori Privilege: Historical Constructions of Maori Privilege circa 1769 to 1940. PhD Thesis Massey University, 2015, pp 177 – 179.

[6] Section 62 Archives NZ R25032083, VHLP491 (Brigid O’Grady’s lease from 1888).

[7] ANZ R25032083, Section 62, Pahiatua Village Settlement, Block XVIII, Mangahao Survey District, VHLP491 Volume 6, Folio 127

[8] Section 63 Archives NZ R25032095, VHLP534 (James O’Grady’s lease from 1899).

[9] Michael (Mick) Joseph Kelly was born in 1886, older brother of John (Jack) Kelly, both born in County Laoise, Portarlington. Mick was in the Hawkes Bay Company Wellington Infantry Regiment Main Body before becoming and engine driver and died 1943 aged 57.

[10] Births Deaths and Marriages, Department of Internal Affairs 1941/2456, Elizabeth Mary Kelly to John Colin Dron (check where they were married as Colin was not a Catholic).

[11] He was born in 1909, and his full name was John Colin Dron.